What happened to the Just Energy Transition grant funding?

- Katrina Lehmann-Grube, Imraan Valodia, Julia Taylor and Sonia Phalatse

Researchers take a closer look to determine who the money has gone to, when it was disbursed, and what it was spent on.

At COP28, the annual climate change conference which was held in Dubai at the end of 2023, the government released two key documents for the Just Energy Transition in South Africa. The first was the Just Energy Transition Implementation Plan, the roadmap for achieving decarbonisation of the economy in a just manner. The Implementation Plan covers six portfolios: Electricity; Mpumalanga Just Transition; New Energy Vehicles (NEVs); Green Hydrogen; Skills; and Municipalities and it has incorporated some of the comments received during the consultation process on the Just Energy Transition Investment Plan.

The second was the Just Energy Transition grants register. This document tracks how the grant allocation as part of the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) has been spent.

The JETP was announced with great fanfare at COP26 in Glasgow in 2021. It is an $8.5-billion funding package from the European Union, Germany, France, the US and the UK (subsequently the Netherlands and Denmark have also joined) to help South Africa achieve a just transition in the energy sector. This partnership has received substantial criticism for the small proportion of grant financing that was allocated – only 4% of the total amount – with the vast majority coming from concessional loans instead.

The grant register tracks this grant allocation in a bid for greater transparency within the just transition processes, which is to be commended. It tells us who the implementing entities are, the priority areas for the funding, the partners and other beneficiaries, the amount in rands and US dollars, and start and end date of the projects.

This is an important step in a set of just transition financing processes that have been shrouded in secrecy (until the point where final documents are released). However, others have already raised concerns about how this money has been spent, and what this means for the just transition as a whole in South Africa. As stated by director of Just Share Tracey Davies: “What’s staggering is that there has been no transparency around recipient and project selection. This raises the question whether only entities with the right connections have been able to access funding.”

In this piece, we take a closer look at the data in the register and some of the key trends, to determine who the money has gone to, when it was disbursed and what it was spent on.

The total amount accounted for in the grants register is R10,072,283,749, just more than R10-billion. This covers more than the original 4% stipulated in the Just Energy Transition Investment Plan – $329.7-million, which is R6.3-billion at the current exchange rate. This is presumably due to the addition of funds from the new partners. However, this too is unclear. There is a concern that the register may therefore include projects that were already happening anyway, representing funding that is neither new nor additional, a problem within climate finance more broadly.

Where has the money gone?

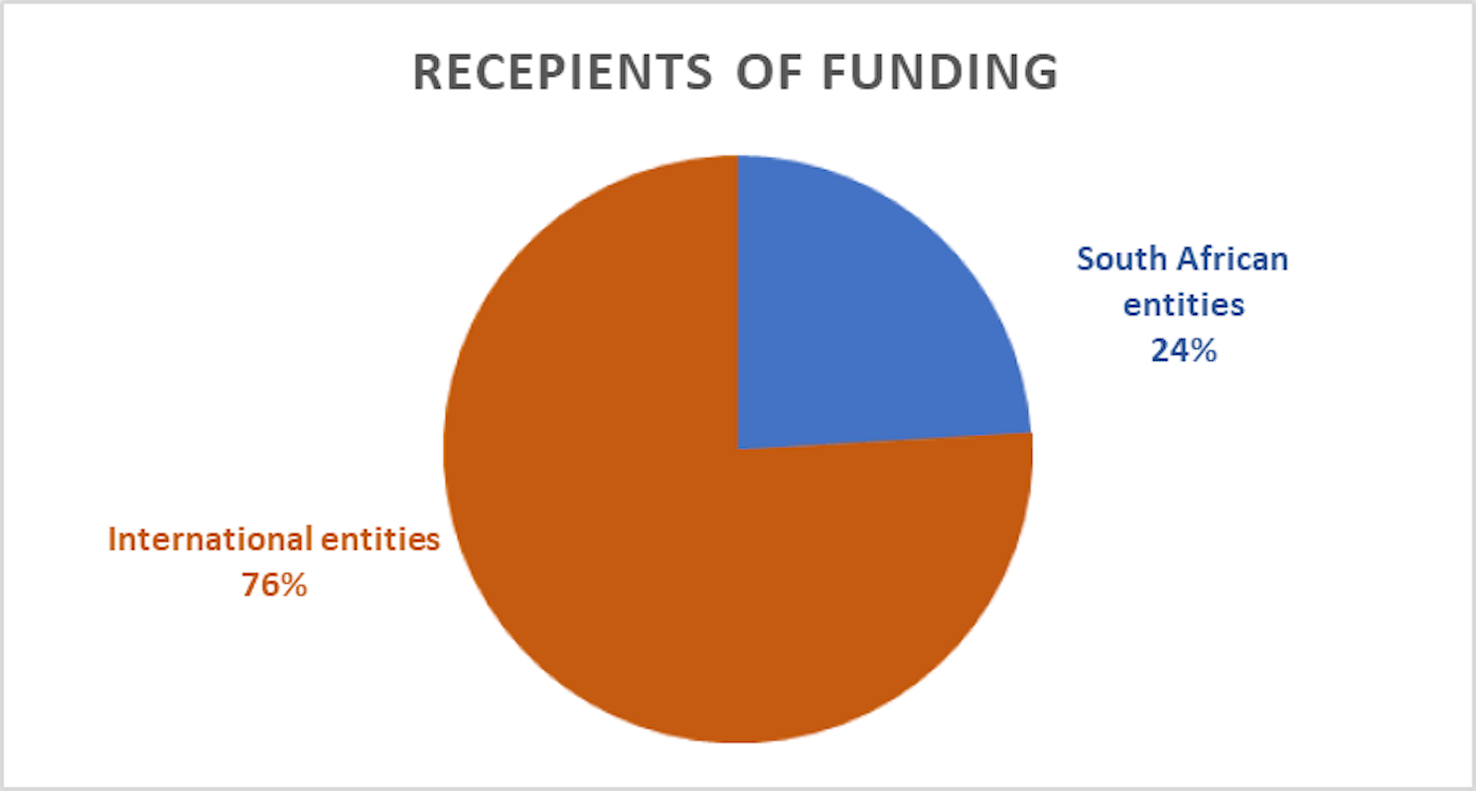

Recipients of Just Energy Transition grant funding. (Source: Authors’ calculations)

The register distinguishes between implementing agencies and “parties and other key beneficiaries”. Only 24% of the money goes to South African implementing entities (a mix of private companies, non-governmental organisations, universities and government bodies). The rest goes to foreign companies and organisations, in most cases to entities from the donor countries. For example, about R1.7-billion goes to GIZ, the German development agency, and R2-billion to KfW, the German development bank. Therefore, more than R3.7-billion, which is more than a third of the total grant financing and covers all the grant financing given by Germany, goes straight back into its own development agencies and bank (and a handful of German research institutions). When asked about this at COP28, a German official stated that obviously this money is only going through these agencies as they are just the implementers and not the final beneficiaries. However, this then acts as a mask for where this money really goes, defeating the transparency goal of the register. In most cases, these agencies take a significant cut of the funds to cover their own (substantial) costs and often hire their own consultants to support the work. A key question is what proportion of these funds trickles down to the final beneficiaries.

Although not quite as bad as the German case, this pattern is seen across the board. From the US’s funding, R145-million goes to Deloitte (out of a total of R222-million going to consulting and financial advisory firms) and R58-million to the US Department of Energy’s National Labs. Other countries are also sending money to their own government departments – such as the Danish Energy Agency and the Dutch Water Authorities.

While the final beneficiaries of the activities in the European and American entities may well be South Africans, there is no evidence currently that this is the case.

When was the money spent?

More than R8.5-billion has been used for projects which are already complete. And only two projects, out of a list of 145, had not started yet at the time of writing. More than half the money (R5.2-billion) was disbursed before November 2022 when the JET Investment Plan was launched for public comment. This means that most of this money was out the door before the public even had a chance to give their inputs and comment on the Investment Plan which dictated the priorities and funding. What exactly was the public consulting on if that money was already spent? Were none of the inputs related to the concerns about the priorities ever going to be considered? Despite the hints at transparency and consultations occurring during the development of the JET Investment Plan and now Implementation Plan, there seems to be a completely parallel and independent process where the money is actually allocated and disbursed.

What was the money used for?

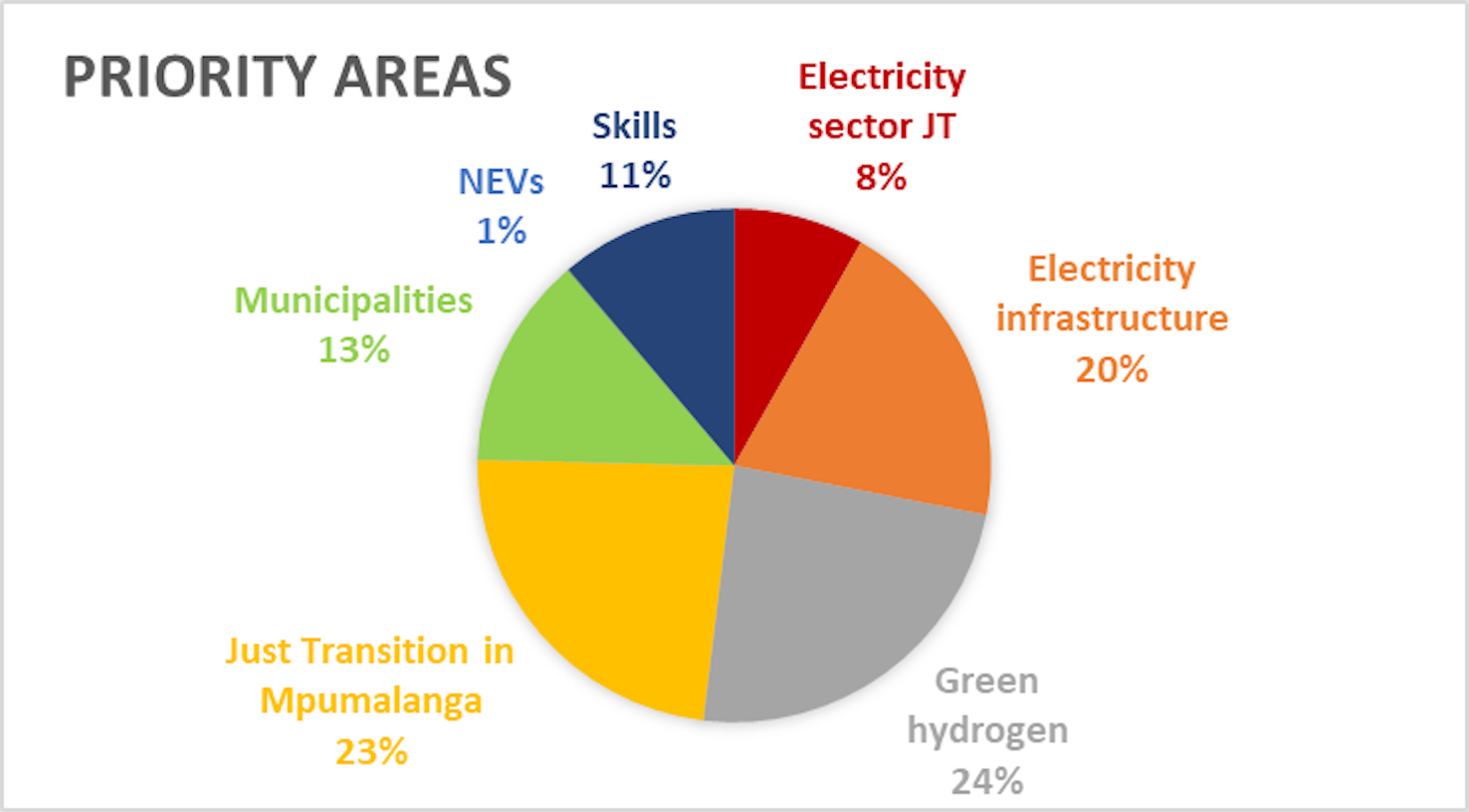

The register stipulates the different priority areas to which the money has been allocated. The majority has gone to green hydrogen, the just transition in Mpumalanga, and electricity infrastructure; with other significant proportions going towards municipalities and skills (see figure 2). However, a closer inspection reveals that much of this finance does not go directly to these priorities.

Just Energy Transition grant spending on different priority areas. (Source: Authors’ calculations)

For example, of the money allocated for electricity infrastructure, almost none is allocated to actually building electricity infrastructure, whether that be new renewable generation capacity or expanded grid infrastructure, both of which are urgently needed in South Africa. Rather, it is spent on a mix of technical assistance, project feasibility studies, scenario projections and capacity building. In total, about R1.2-billion of the grant financing is spent on technical assistance which has long been criticised as a form of aid for being ineffective, extremely expensive since much of these funds go to foreign “experts”, and an outdated form of development.

Additionally, about R1.5-billion is spent on various forms of green finance – green bonds, refinancing of community trust projects, and blended finance/catalytic finance to de-risk and attract private-sector investment. This is arguably not where the grants portion of the finance should be focused.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Our Burning Planet

There are also significant amounts spent on municipalities, stakeholder engagement and capacity building, much of which is sorely needed and should be acknowledged. However, civil society organisations (CSOs) and workers’ unions have been almost completely left out. Only about R41-million has been dedicated to CSOs (0.4%), with an additional R6.4-million going towards research assistance to unions. Most startlingly, there is no money provided for care for workers in affected value chains (as stipulated in the JET Investment Plan), nor social protection more broadly. Skills and training are a key concern for unions and workers in the transition. While R1.1-billion has been categorised as skills funding, only R453-million has gone to actual skills training, with some strange inclusions under the banner of “skills”, such as financing the secondment of an employee of the British High Commission to the Presidential Climate Commission.

There has been a vocal push for more grant financing to both mitigate and adapt to climate change from all sectors in South Africa. However, the benefit of this grant financing lies far out of the reach of those who need it most. It is clear that communities and affected workers have already been left behind. The next stage will be to see where the loan financing is going. From what we have seen so far, there is little reason to be hopeful.

The writers are with the Southern Centre for Inequality Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand. This article was first published in Daily Maverick.