Unless something unforeseen occurs, the shape of post-election South Africa is already reasonably clear - it shows a wounded and decaying ANC.

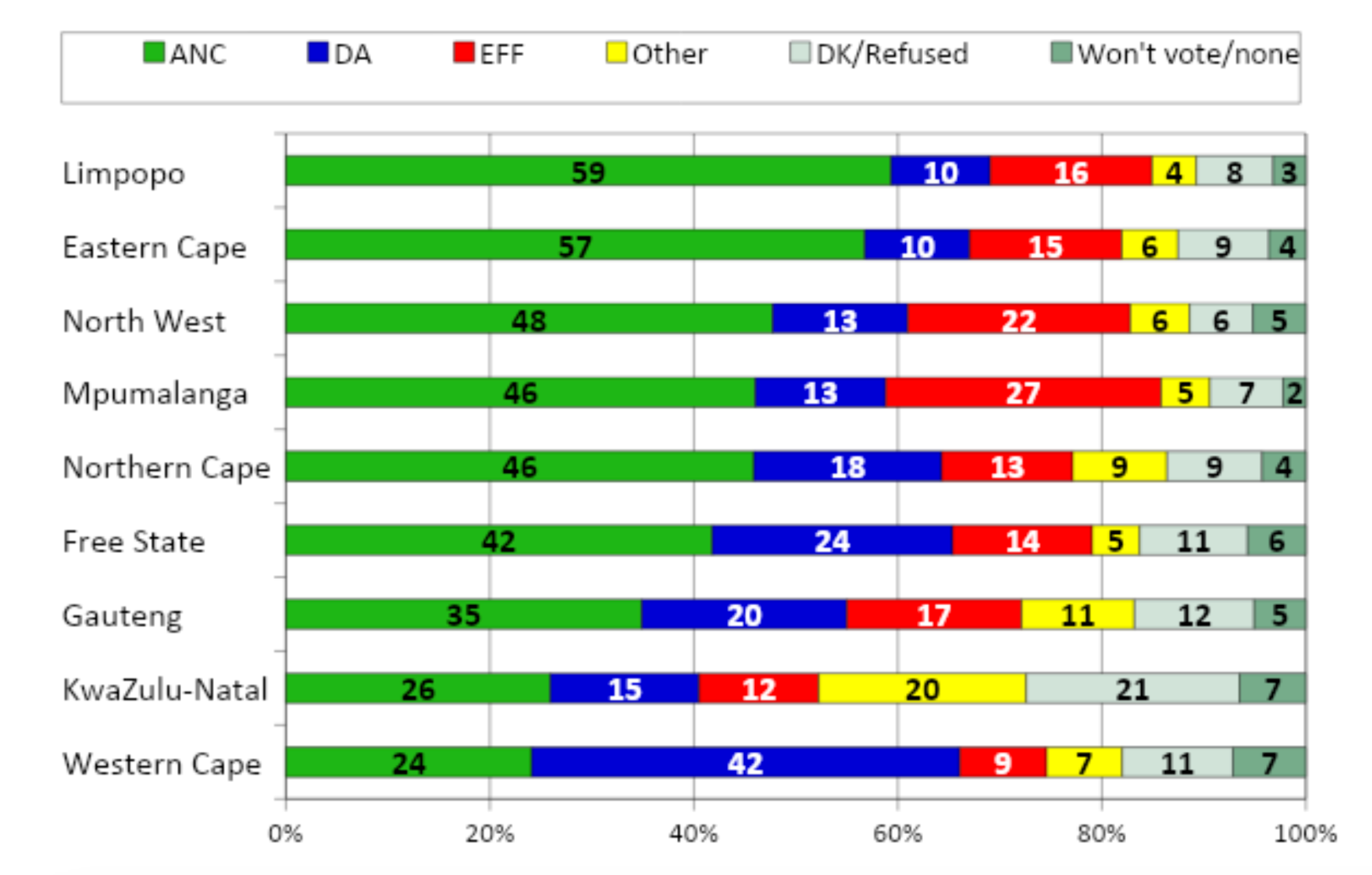

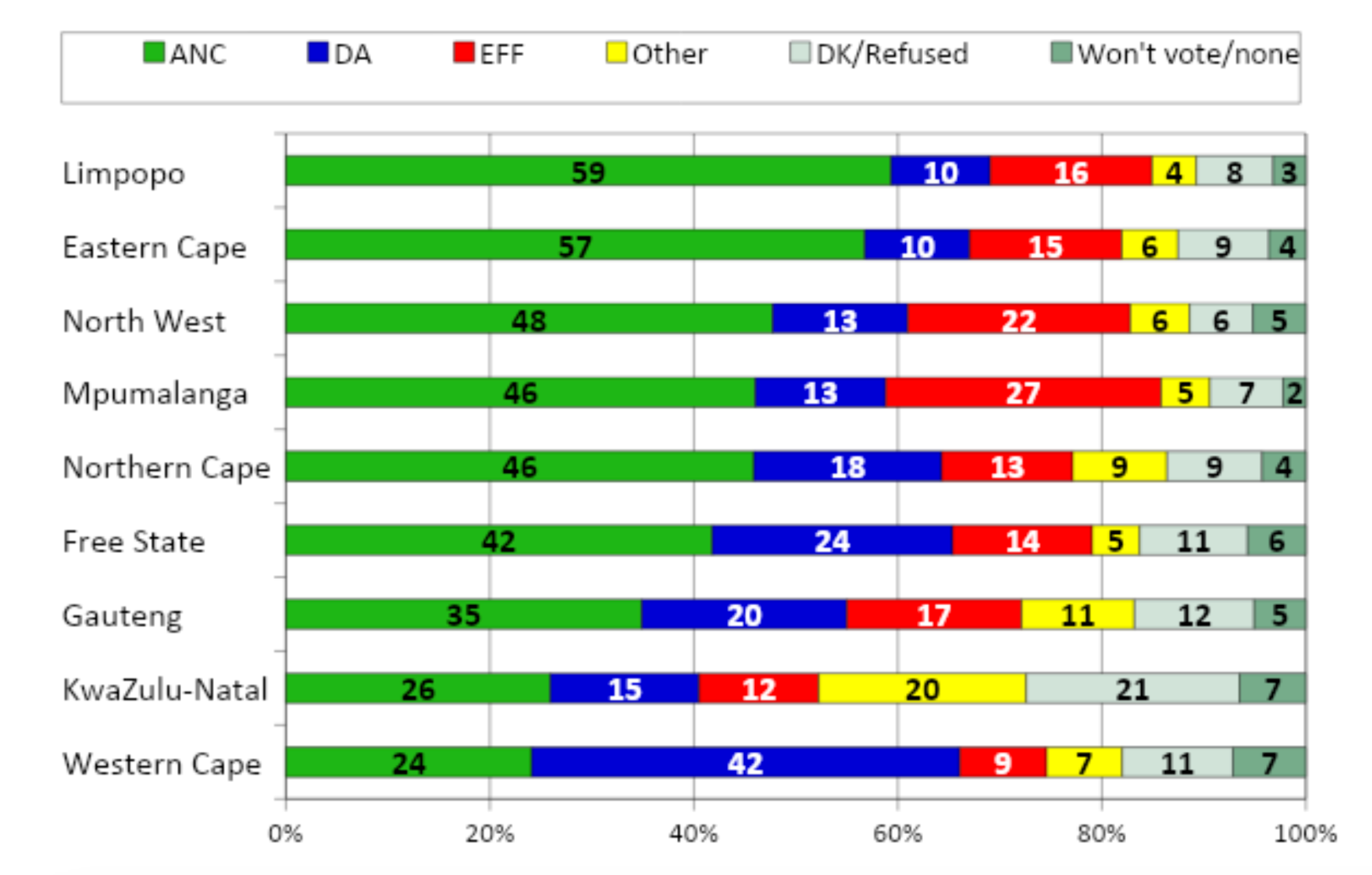

Provincial breakdown of a national poll of voter intentions ahead of the 2024 elections. (All the figures cited are for registered voters only, regardless of voter intention.)

Western Cape

The headline that can be taken from the graph presumably depends on what the reader thinks matters most or where they live. Reading from the bottom up, the first headline is that in this poll, the DA has lost its majority status in the Western Cape.

This downward trend started in 2019, when the DA won a respectable 56%, but down from the 59% in 2014. The current 42% is a quite remarkable drop given the ongoing media coverage of Western Cape governance as the national gold standard – voters seem not to agree.

The ANC in the Western Cape has continued to decline, from 29% in 2019 to 24% – it is only half as popular as the DA. The EFF has almost doubled, but from a small base and still fails to reach double figures in the poll.

In the Western Cape, “other” (7%) comprises some small but important growth points – the ACDP has 1% but so do newer entities, including Build One South Africa, led by the DA’s former leader Mmusi Maimane, and the Patriotic Alliance with a respectable 2%.

Coalition government may have reached the Western Cape, which in addition to 7% choosing small parties, sees 18% undeclared. The DA needs to mobilise roughly half this latter group to breach the 50% mark – if not, it will face difficult choices for coalition partners. This is new territory for the provincial DA, which (in the Western Cape) may be perhaps suffering the “sins of incumbency”.

It is common cause in polling that many voters who tell fieldworkers they “don’t know” whom they may vote for, or refuse to say, do end up voting. Past experience strongly suggests that they are not ANC voters hiding away, but that they largely vote for parties other than the ANC. As such, on election day, all opposition parties, large and small, should win more votes than polled, as people are forced to choose (or spoil their ballot paper).

KwaZulu-Natal

Just above the Western Cape in the graph is KwaZulu-Natal. Recently, Stephen Grootes wrote a piece about the province, wondering what would happen in the election, given the seeming inevitability of the ANC slipping below the 50% mark (it achieved 54% in 2019). The results in the poll are a stark answer – the ANC has collapsed, with a quarter of the vote (26%), a figure that may drop further.

This survey was in the field before former President Jacob Zuma launched the uMkhonto Wesizwe party (MK) and took aim at the ANC (the party and its voters). The voter appeal of MK is currently unknown – but it will be taking away ANC voters.

The EFF has grown by a couple of percentage points, as has the DA: again, neither of the two pretenders is making much of a showing.

The real twist is provided by the Inkatha Freedom Party, which dominates the “other” category at 15%. That means the IFP and DA are level-pegging. The province has a whopping 28% of respondents who did not select a party in the survey: this makes any firm predictions impossible, but the pattern of a collapsed ANC vote and other parties juggling for voters will not change. Nor will speculation over the fascinating set of possible coalitions that will govern the province.

Gauteng

Gauteng is the third province where the ANC fails to hit the 40% mark, coming in at 35%, a calamitous drop from the 50% of 2019. As in KwaZulu-Natal, it may still be the biggest party, but the trend suggests it is becoming a small(ish) fish in a big pond. With the EFF on 17% and the DA on 20% in Gauteng, the coalition prospects can go either way – though the ANC remains the decider.

If an ANC/DA or ANC/EFF coalition emerges, the smaller parties will lose influence (ActionSA has 3%, the IFP 2%, the Freedom Front Plus 1% as do Build One South Africa and the Patriotic Alliance). They will be neither king-makers nor coalition makers or breakers.

The 17% of Gauteng respondents who declined to choose a party have historically voted against the ANC – so there may yet be growth among smaller parties as well as the DA and EFF.

Free State

The Free State has emerged as a province of interest. The ANC finally breaks through the four-in-10 barrier, at 42% – again, a dramatic drop from the 61% of 2019, with former Premier Ace Magashule possibly muddying the waters for the ANC. The DA and EFF have yet again managed steady if unspectacular growth – and again, governing the province will be undertaken by a coalition chosen by the ANC, not the opposition.

Who’s the boss?

That seems to be the key take-away: provinces are beginning to slide from the ANC’s grasp, but in five of nine provinces, the ANC remains large enough to dictate coalition terms. These results suggest that KwaZulu-Natal has now joined the Western Cape as being beyond the reach of the ANC.

In Gauteng, the ANC remains large, but the behaviour of the 17% undeclared voters will have a significant impact. If those voters all vote, and vote non-ANC, this will test Gauteng ANC politics – will it govern with the DA or the EFF; and will it follow national guidelines on this issue, or follow its own path and dare the centre to respond?

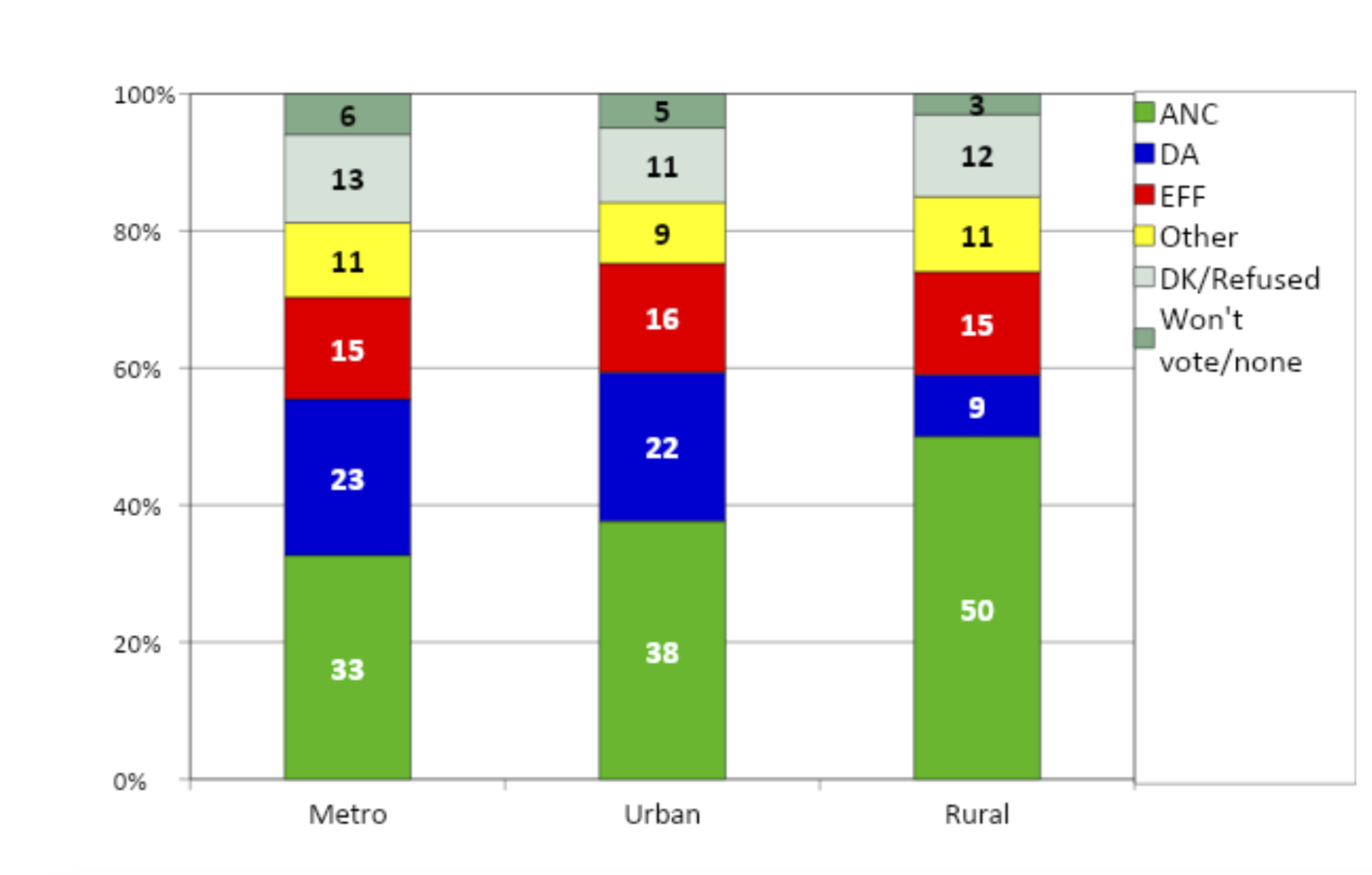

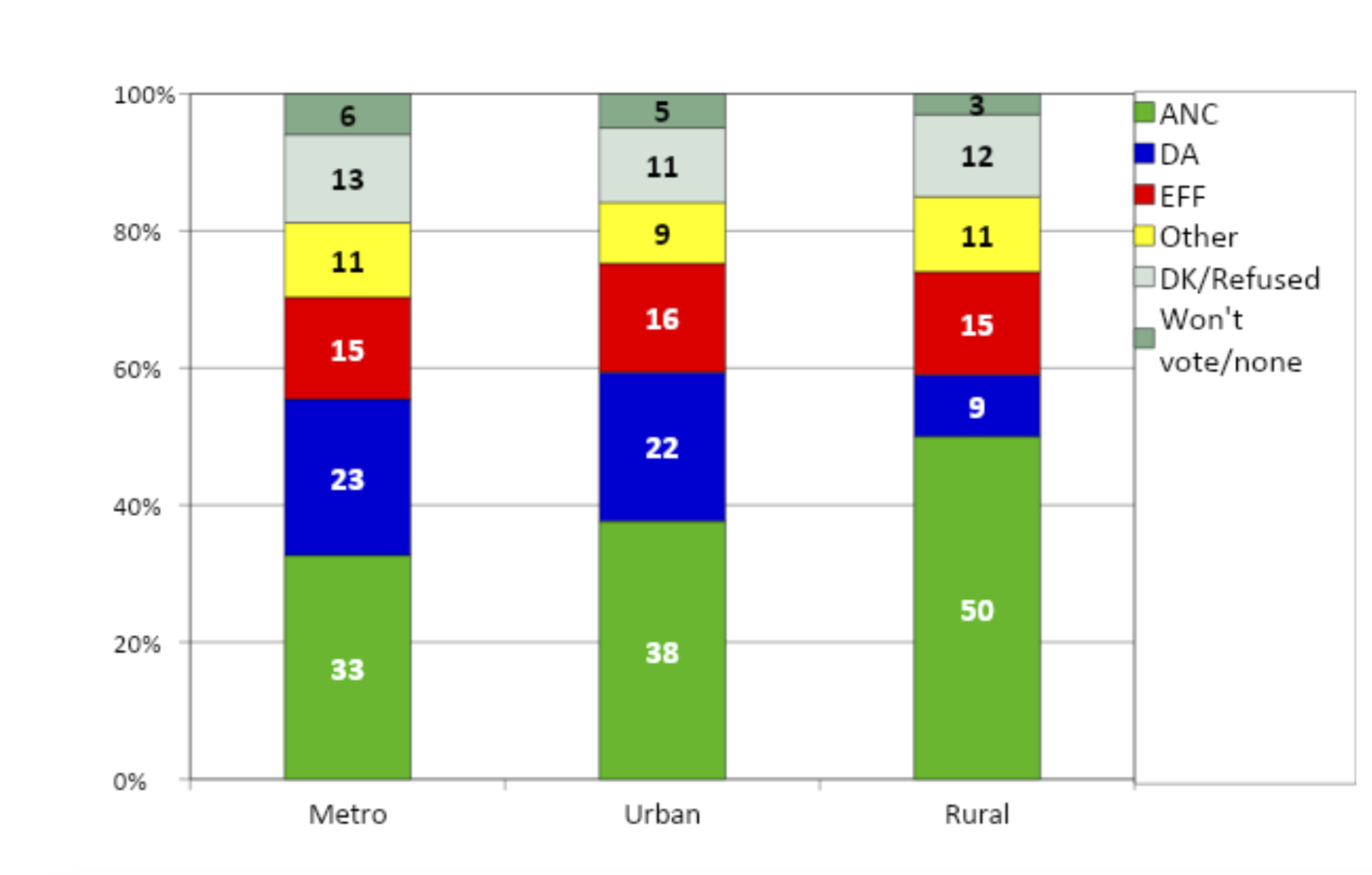

Rural or urban

Finally, the graph makes it clear that the ANC is fast becoming a rural party. In metropolitan areas the ANC is a minority party at 33%, just 10% ahead of the DA. In peri-urban areas, the ANC fares slightly better, at 38% – but the DA and EFF remain constant, with fewer respondents refusing to answer the voting question and fewer selecting smaller parties. As urbanisation continues apace, this trend can reasonably be expected to grow, and the ANC should be concerned.

In rural areas, the ANC stands at 50% – the DA clearly has little rural purchase; the EFF does better, but no one other than the ANC has managed to capture the political imagination of the majority of rural voters.

That said, the ANC should still worry: rural areas, and predominantly rural provinces, have always been its most loyal base. But when it can only muster support in the upper 50% range in Limpopo (59%) and the Eastern Cape (57%) – and drops below the 50% threshold in every other province – all the trends are bad news for the ruling party.

Finally, the EFF performance is important – but is not a profound change to electoral politics, despite media attention and speculation. EFF support remains constant whether metropolitan, peri-urban or rural. It has grown in every province, but is stuck well below the 20% mark nationally, though it has breached that figure in Mpumalanga (27%) and North West (22%).

It is outperforming the DA in four provinces, and may soon challenge the DA as the official opposition in South Africa. Yet the growth of the party is far from stellar: it is incremental, growing by a couple of percentage points here and there, and seems to have a vote ceiling just as the DA does.

As the ANC decays, the DA and EFF are fighting hard – but neither is able to persuade more than a fifth of voters (nationally) to vote for them. The new parties are barely registering on the voting map.

The new world is indeed struggling to be born.

David Everatt is a Professor at the Wits School of Governance. This article was first published in Daily Maverick.