Half of all South Africans are overweight or obese

- Sameera Mahomedy

The increased availability and consumption of unhealthy food have contributed to poor health outcomes, and warning labels on unhealthy foods help change that.

South Africa’s national health department recently invited public comment on regulations for warning labels on food packaging. The regulations specify how pre-packaged food should be labelled. Broadly speaking, “front-of-pack” labels provide information about the overall nutritional quality of foods and beverages.

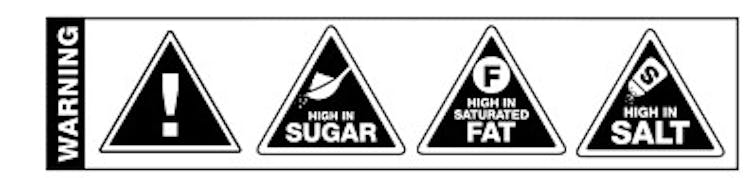

The aim is to allow consumers to make healthier food choices. The proposed rule is that food products containing added saturated fat, added sugar, or added sodium, and which exceed prescribed cut-off values, must have a warning label.

Globally there’s been an increase in the availability and consumption of unhealthy food. This has contributed to bad health outcomes, including a rise in overweight and obesity.

Unhealthy diet is a major risk factor for noncommunicable diseases such as heart attacks, cancers and diabetes. People who are overweight or obese are at greater risk of developing these conditions.

The figures in South Africa are especially worrying. Half of all adults are either overweight (23%) or obese (27%). Noncommunicable diseases account for 59.3% of reported deaths in the country.

The effectiveness of front-of-pack warning labels is supported by international evidence. The adoption of these nutrition warnings can help combat obesity, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and some cancers. Several countries have introduced them, including Singapore (1998), Thailand (2007), Chile (approved in 2012, implemented in 2016), Ecuador (2013), Indonesia (2014), Mexico (2016) and Colombia (2022).

Local evidence has supported international evidence and found that South African consumers have a positive attitude towards warning labels on ultra-processed foods and drinks. When asked if they would be open to having warning labels on food, study participants said that warning labels were easy to understand and would assist them in quickly identifying unhealthy products.

The content of the regulations

In addition to the warning labels, the regulations also introduce marketing restrictions.

Regulation 52 relates to any packaged food with front-of-pack warning labels. The regulation limits the advertisement of these foods in various ways. It prohibits the use of celebrities and cartoon characters, competitions, gifts, collectable items and other items that may appeal to children. The abuse of positive family values to encourage consumption of unhealthy food is also prohibited. The advertisements are also required to have a warning.

This is line with the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) recommendations to implement evidence-based policies, which include mandatory front-of-pack warning labels and marketing restrictions on unhealthy foods and beverages. In particular, the WHO has noted that an unhealthy food environment includes the promotion or marketing of unhealthy foods and has linked this to the undermining of children’s rights.

In my opinion as a public health law and policy researcher, some aspects of the regulations deserve commendation.

The first is the fact that the front-of-pack warning labels are mandatory. This allows for the regulation of unhealthy products that play a role in noncommunicable disease development.

The second relates to the inclusion of a mandatory warning icon for sweeteners alongside sugar, salt and saturated fat. These are important food components to regulate, considering the noncommunicable disease and obesity crisis in South Africa.

In addition, the limitations and prohibitions on when nutrition and health claims can be made are beneficial. In particular, section 50 states that products required to have a warning label may not include any health claims.

Another noteworthy inclusion is the fact that exceptions have been made for small-scale producers. This removes a potential barrier to South Africa’s informal food economy and small and micro food businesses.

What’s missing

There are a few areas of the regulations that could potentially be strengthened.

To give effect to the purpose of the marketing restrictions, the regulations should define advertising or advertisements. We, at the SAMRC/Centre for Health Economics and Decision Science, propose looking at the law in Chile. It defines advertising to include all forms of promotion, communication, recommendation, propaganda, information or action aimed at promoting the consumption of a certain product.

The section that restricts the use of competitions, tokens, gifts or collectable items which appeal to children is a great addition. This section should be clarified to ensure that in this context children are understood as persons under 18. This will align with the Constitution of South Africa and the Children’s Act 38 of 2005.

The regulations should prohibit depicting children on products which carry a front-of-pack warning label. Any advertising in places where children gather, like schools and clinics, should also be prohibited. These are both restrictions suggested by the WHO to protect children from the harms of marketing.

To ensure that this regulation is effective, the Department of Communications and Digital Technologies and the Department of Education need to extend the protection of children from unhealthy foods and beverages as part of their mandate. This will allow for more comprehensive restrictions.![]()

Sameera Mahomedy, Researcher in Law and Policy, SAMRC/Centre for Health Economics and Decision Science - PRICELESS SA, University of the Witwatersrand. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.