Nation building debate is still relevant today

- Edward Webster

New book by scholar Mandla Radebe reminds us of the debates by an idealistic generation committed to building a non-racial SA.

There has been much comment recently on the lack of representation of minorities in the leadership structures of South Africa’s governing party, the African National Congress (ANC).

For Douglas Gibson, a former leader of the opposition Democratic Alliance (DA), the exclusively black composition of the ANC’s top leadership shows that the ANC is no longer committed to building one nation. He believes

the ANC is clearly not a home for all. Look at its MPs, ministers, MECs, councillors, and mayors … The leadership has place only for black South Africans.

For Gibson, the baton has been passed on to the DA.

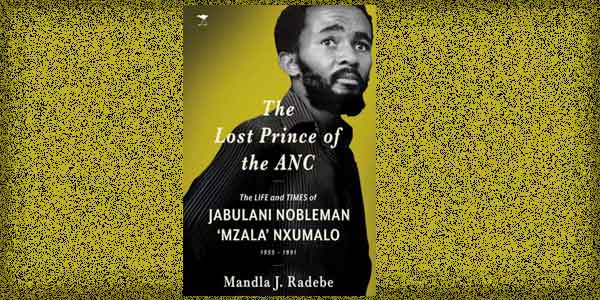

At the centre of this debate is the “national question”, the drive to build one united democratic nation. This debate has been captured in the scholar Mandla Radebe’s fascinating biography, The Lost Prince of the ANC: The Life and Times of Jabulani Nobleman “Mzala” Nxumalo, 1955-1991.

The book does not only begin to fill a gap in liberation history. It also reminds South Africans of the rich and robust debates that took place by an idealistic generation committed to building a non-racial South Africa. It is a legacy that the ANC needs to recover if it is to rebut those who argue that it is no longer a “home for all”.

Who was Mzala?

Mzala was something of a cult figure in ANC circles, celebrated for his intellectual insights. But his premature death at the age of 35 makes him a relatively unknown figure outside the party.

Born and brought up in a closely knit and deeply religious family in rural KwaZulu-Natal, Mzala showed a close interest and ability in scholarly pursuits at an early age. Forced into exile after a student revolt at the University of Zululand in 1976, he rapidly emerged as a leading grassroots intellectual within the ANC and its ally, the South African Communist Party (SACP). He was prolific in his writings and the range of issues he touched on.

The great value of Radebe’s book is that it offers the reader a rounded picture of a revolutionary of many unexpected dimensions. He was deeply committed to his family and strongly influenced by his Christian upbringing. His passion was music and the Amandla Cultural Ensemble of the ANC, a cultural group that through its music, poetry, theatre and dance, was used to mobilise international support for the struggle against apartheid.

But what stands out in Radebe’s biography is Mzala’s contribution to debates on Marxist theory inside the ANC. It was three-fold.

Firstly, he regarded the working class as the driving force of the revolution. Secondly, the motive force behind the revolution was not the exiled leadership, but the masses back home.

History’s great call to our movement is to begin a process of de-exiling ourselves, of transferring the initiative of the liberation process to the actual arena of our struggle, inside South Africa (page 143).

But his major contribution was on the difficult debate on the role of ethnicity. Mzala unequivocally wrote that

our democratic republic will definitely develop the positive aspects of my Zulu culture, language and so on, so that I, together with those of my ethnic group, can contribute a cultural flower to the banquet of South African culture (page 236).

In the words of Essop Pahad, who worked closely with Mzala in exile and was later appointed the Minister in the Presidency under Thabo Mbeki:

Perhaps the greatest loss of all is to our party’s ongoing attempts to indigenise Marxism-Leninism on South African soil (page 4).

For Mzala, some members of the communist party, such as the doyen of South African Marxists Harold Wolpe, decentred “race”. Indeed, Radebe reports that Mzala rejected Wolpe as a supervisor of his PhD as he “felt that Wolpe downplayed the role of race and elevated class in the debate” (page 238).

Sadly Mzala never completed his PhD, and the reader is left not knowing what a scholarly version of his argument would have been. However, Radebe does provide a clue by giving us the working title of the thesis, “Ethnicity and the problem of nation-formation in South Africa”.

Intellectual contribution

What made Mzala’s intellectual contribution distinctive was that it combined a sophisticated grasp of revolutionary theory with a practical engagement with the reality of ethnic nationalism in KwaZulu-Natal. This emerges most clearly in his best-known work, Gatsha Buthelezi: Chief with a Double Agenda. The power of Mangosuthu Buthelezi, as leader of a Bantustan – impoverished areas where the apartheid state decreed blacks belonged to distinct ethnic states, separate from each other and from whites – depended on the apartheid state.

As pressure on the state grew due to internal resistance to apartheid and sanctions from abroad, Buthelezi came to be regarded more and more as a government puppet. His emphasis on Zulu identity over national unity led eventually to a virtual civil war between his Inkatha Freedom Party’s mainly Zulu loyalist supporters and ANC members in KwaZulu-Natal and parts of Gauteng province.

Mzala rejected this narrow view of ethnic identity, most clearly expressed (page 8) by Mozambican revolutionary Samora Machel:

For the nation to thrive the tribe must die.

Mzala’s more nuanced approach is captured when he wrote (pages 2020-1):

Denunciation of tribalism and ethnic exclusiveness is not denunciation of the ethnic communities themselves. People’s democracy does not mean that all cultural and traditional distinctions between the various groups must disappear … what is not needed are bantustans to preserve their cultural heritage.

This is why it is important to revisit Mzala’s writings; it reminds all South Africans of the central goal of building one nation in all its ethnic diversity.

Recovering the nation-building project

The “national question” as it developed in South Africa went well beyond the debate around Buthelezi’s Inkatha and Zulu identity; it was and is a debate about who constitutes the South African nation. For example, the Western Cape Province, which post-1994 has seen sharpened racial tension, is populated by a majority of “coloureds” with “Africans” and “whites” as minorities.

In light of the ANC’s nation-building project, how should these tensions be understood? Does their manifestation show an unresolved national question, activist and democratic Marxist Mazibuko Kanyiso Jara (2002) asks, or a failing nation-building project?

Although the ANC has often equivocated historically on how best to deal with minority groups, its vision of building one nation has been a crucial contribution to the liberation struggle. By recovering the lost debate on the “national question” through this comprehensive biography of Mzala, Mandla Radebe has reminded us of the ANC’s historic aspiration to build one united non-racial nation.![]()

Edward Webster, Distinguished Research Professor, Southern Centre for Inequality Studies, University of the Witwatersrand. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.