Why dissecting stories about garbage in popular culture matter

- Mehita Iqani

From oil disasters in Mauritius to street artists in South Africa, the story of rubbish in the media helps shape popular culture and environmental change.

Rubbish has become an integral part of everyday life. Think about it. How many things did you throw away today? And this week? In the last year?

Some study rubbish directly – seeing it as contemporary archaeological evidence for society. But how people talk about rubbish through media platforms also deserves attention. This is because it’s increasingly relevant to the task of solving the environmental problems facing humanity.

A range of environmental issues have been capturing attention in the media recently. Many of these are linked quite directly with consumer culture, for example, campaigns to ban plastic straws and concern with how the COVID-19 pandemic has caused new forms of littering of single-use masks and gloves.

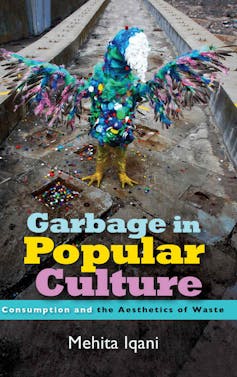

In my new book Garbage in Popular Culture I explore three key ways in which garbage narratives come into pop culture. The first is linked to activism, the second to hedonism and luxury, and the third to anxieties about the environment.

Activism

The first theme that I explore is activism around environmental issues related to waste.

The aphorism “reduce, reuse, recycle” is well known. Some individuals – notably the more well off – put much effort into reducing waste. For example, New York social media heroine, Lauren Singer, known as “Zero Trash Girl”, made a media project and career out of living her consumer lifestyle in such a way as to not produce any trash. She famously produced only a glass jar’s worth in four years.

Others create fine art out of rubbish. South African street artist r1 spearheaded the creation of collaborative public installation called iThemba Tower, which wrapped a defunct communications tower in Johannesburg with plastic bottles, filled with messages to the future. His re-use of rubbish turned it into a medium of communication.

Recycling gets a lot of attention. But it is a classed, and often gendered, occupation. Consider the labour of a cooperative of women recyclers based in Pune, India, and the self-organising work of the African Reclaimers Organisation in Brixton, Johannesburg.

Hedonism

The second theme I explore is how hedonistic consumption by wealthy consumers is a key source of rubbish. Media coverage of the post-party landscapes of two entertainments festivals – Glastonbury Festival in the UK and Afrika Burn in South Africa – reveals two quite different attitudes towards the moral responsibilities linked to trash.

Glastonbury, although trying to change this, used to be known for the appalling litter-scapes left behind by revellers. Afrika Burn attempts to inculcate a culture of radical responsibility for party-goers to move their trash off site.

In relation to tourism, media narratives about trash on beaches on tropical islands reveal how a clinical and persistent removal of trash is necessary to maintain the advertised fantasy of an idyll untouched by waste.

Together, these studies show how, most often, it is the poor who are expected to live uncomplainingly alongside garbage, while the rich expect it to be cleaned away for them.

Angst

Media narratives about massive environmental disasters lead us into the realm of collective existential angst, the third theme in the book. The age of the Anthropocene, that is, the epoch in which human activity has radically altered the make up of the planet and climate, has seen the devastation of natural environments through fossil-fuel based waste: specifically, oil and plastic.

A recent incident in Mauritius highlighted the devastation caused by oil spills. The largest spill ever at Deepwater Horizon became the subject of many film and TV narratives. These allow us to consider how it’s impact was publicly processed in different ways.

In many visual narratives of huge oil spills and so-called “plastic islands” the scale of the devastation that the human race has created is presented as unfathomable, almost beyond representation. Instead of offering a coherent place from which we can consider and act, this “new” sublime is a terrifying edge that we ourselves have created. We know that there might be no coming back from the abyss of climate change and a planet now carrying more man-made substances than biological life.

This creates significant collective distress about our future and that of our planet.

Rubbish is the most public of all objects. Media narratives can invite us to respond to it with with hope or it can lead us towards being paralysed by dismay.

Media discourses and communicative forms have the potential to contribute positively to new shared ideas (and perhaps behaviours) about rubbish.

The new book Garbage in Popular Culture: Consumption and the Aesthetics of Waste is available from SUNY Press.![]() Mehita Iqani, Professor in Media Studies, University of the Witwatersrand. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Mehita Iqani, Professor in Media Studies, University of the Witwatersrand. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.