What South Africans must do to avoid a resurgence of COVID-19 infections

- Laura Rossouw and Carmen S. Christian (PhD)

It is key to continue high-impact non-pharmaceutical interventions that will not impede economic activity, but limit the spread of COVID-19.

South Africa’s stringent lockdown earlier this year may have saved lives by containing the spread of COVID-19. New COVID-19 infections have been declining and lockdown restrictions relaxed. But this has triggered fears of a new wave of infections.

Several countries have experienced a spike in infections following the easing of harsh lockdown measures. These include South Korea, Canada, Spain and the UK. Health systems are once again becoming overwhelmed, and countries have resorted to stringent lockdown measures once again.

The new round has been characterised by increases in cases – mostly driven by infections among younger groups – but not necessarily increased deaths.

To understand how the country might avoid this it’s useful to look at patterns of behaviour among South Africans after the initial easing of lockdown restrictions from level 4 to level 3 on the 1st of June. A further easing was introduced on the 17th of August, moving people from level 3 to level 2. This left only a few restrictions in place, such as mandatory mask-wearing, no international travel and a six-hour curfew at night.

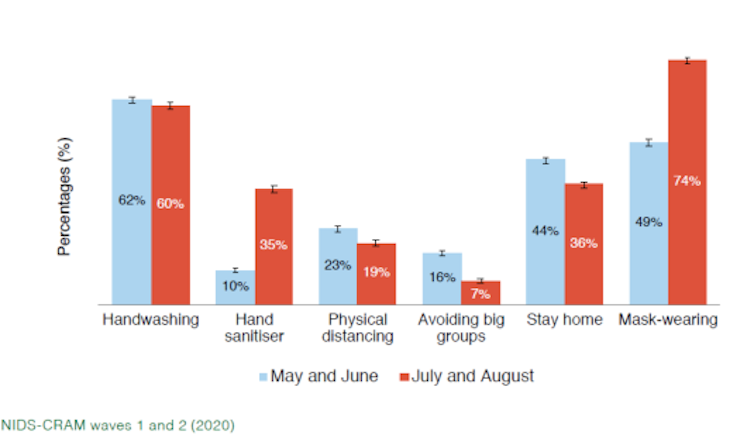

In a survey done during July and August we found that more people were wearing masks than was the case when we conducted the survey in May and June. But this was coupled with a significant decrease in staying at home.

The survey findings signal trade-off in behaviours. This doesn’t bode well for the country as people adjust to life with virtually no restrictions. It is key to continue high-impact non-pharmaceutical interventions that will not impede economic activity, but limit spread. These measures include wearing masks, handwashing and physical distancing.

More must be done to re-inforce these preventative behaviours to avoid a surge in infections. This is particularly urgent given that South Africa’s early strict lockdown resulted in tremendous social and economic costs to the country.

But for these to be effective, high levels of public adherence are required. For instance, research has shown that to flatten the infection curve, 80% of the population must wear masks.

Why human behaviour matters

Human behaviour has been shown to play a significant role in the spike of infections, commonly referred to as the second wave. As restrictions on movement have been relaxed, social activities have increased. In South Korea, nightclubs have been identified as one of the biggest COVID-19 clusters in Seoul. There have also been outbreaks at several churches.

An increase in social night life has also been identified as a significant contributor in Spain. A recent cluster outbreak at a nightclub in Cape Town may signal the start of similar events in South Africa.

The findings of the survey we conducted don’t bode well.

As part of the National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM), we measured the adoption of non-pharmaceutical interventions between May and June; as well as July and August in South Africa.

The broadly nationally representative panel survey collected information on 7,073 South Africans in May and June. Follow-up surveys were conducted with 5,676 individuals in July and August. The two surveys coincided with the relaxation of lockdown regulations from alert level 4 to alert level 3. This included a return to economic activity for more jobs, outdoor exercise, reopening of restaurants and the gradual return to schools.

Our study found that between May/June and July/August this year, self-reported mask-wearing increased from 49% to 74%. The use of hand sanitisers increased from 10% to 35%.

But over the same period there was a drop in physical distancing (23% to 19%), avoiding large groups (16% to 7%) and staying at home (44% to 36%).

The one silver lining was that there was little evidence of respondents placing their trust in poor science. In the July/August survey less than 2% of respondents reported protecting themselves against COVID-19 by drinking hot lemon water and eating garlic. The number was only 1% in the earlier survey.

Going forward

The concern is that non-pharmaeucital interventions adherence among South Africans may decrease over time. Mask-wearing and physical distancing are among the more cost-effective and least disruptive measures of mitigating the risk of infection. As South African policy makers err on the side of caution and take steps to prepare for another wave of infections, non-pharmaceutical intervention adherence should remain top of mind.

COVID-19 messaging must continue to highlight the importance of adherence to these interventions. Wearing masks and avoiding large gatherings should be considered the social norm. The South African government’s mandatory mask-wearing policy, published in July this year, should therefore remain in place until a vaccine is accessible to all.

Messaging should target young people, warning them about the danger of transmitting the disease to vulnerable groups, including populations older than 60 and those with comorbidities.

Non-pharmaceutical intervention messaging should also contain specific and actionable recommendations, as these have been found to be more effective than generalist recommendations. For instance, messaging that reads “wear a mask when you go shopping” may be more effective than just “wear a mask”.

South Africa is a long way off from being able to rely on immunity from infection. In any event, the evidence on whether people can contract COVID-19 twice is still mixed, and accurately measuring immunity to the virus is difficult.

This underscores the need to take the precautions that have been shown to slow the spread of infection. This will not only reduce the number of people dying from the disease. It will also mitigate against the need to impose tough new restrictions on economic activity.![]()

Laura Rossouw, Senior lecturer and Health Economist, School of Economics and Finance, Wits University, University of the Witwatersrand and Carmen S. Christian (PhD), Lecturer and Researcher, Department of Economics, University of the Western Cape. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.