America’s inflection point: four key things Africa must watch for

- John J Stremlau

Many political issues in the 2020 US election are domestic. But black resistance to white supremacy has long had global repercussions.

African scholars and policymakers face a tough challenge in analysing how the US presidential election on 3 November might affect Africa-US relations.

This is because of the extreme polarisation of politics that has been growing for decades in the US. Simultaneous national crises have made matters worse. These suddenly erupted over the handling of the coronavirus pandemic, its impact on the economy, and fresh evidence of white racism towards black Americans.

In deeply divided America, four clusters of political political conflicts arise over issues of national identity, sustainable democracy, international relations and electoral integrity. Crises in public health, the economy and race relations are adding to these conflicts.

African countries struggle with similar political issues – though in very different local circumstances. They are also afflicted by the global COVID-19 pandemic and economic crises.

These four unresolved and contentious clusters of political issues have confronted the US since it declared independence from Britain in 1776 and created a federal state in 1789. In 2020 many crucial issues have yet to be resolved.

Republican President Donald Trump and his deputy Mike Pence campaign for an ethnic nationalist identity. Their appeal is to white Christian racial supremacists. They also advocate a nationalist and unilateral foreign policy. They back Republican efforts to limit equal voting rights. And they threaten other actions to subvert electoral integrity.

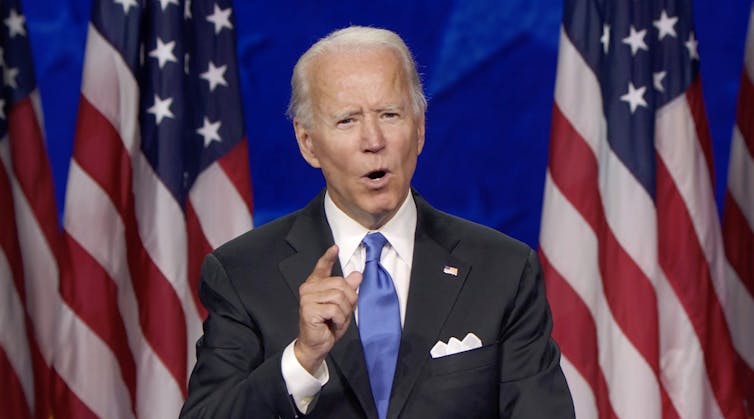

Their Democratic challengers Joe Biden and Senator Kamala Harris have very different goals. They are campaigning for an America that is more inclusive and equitable. A similar aspiration is enshrined in South Africa’s constitution: to become a country that belongs to all who live in it, united in its diversity.

American inflection point

Harris describes the 2020 election as an “inflection point”. She means a turning point in America’s long curve towards or away from democratic development. It is a nod to an adage attributed to Martin Luther King, and popularised by former President Barack Obama, that:

The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.

This theme threads through the Democratic Platform, with specific promises. Biden and Harris now appear likely to be elected. It’s therefore important to consider what their positions mean for Africa-US relations.

Trump, by contrast, repeats his promise of 2016 to restore America’s “greatness”. His Republican Party doesn’t even offer a new list of goals and programmes for the next four years. Instead, the party republished its 2016 platform with a covering memo praising the leadership of Donald Trump. This leaves voters and foreign governments with little new to analyse.

For those trying to calculate the effects on African nations of an American inflection point, there are four areas to consider:

National identity

White supremacy has been the predominant national identity since America was colonised in the 17th century. Now, with ethnic diversity accelerating, exemplified by the election of a black president in 2008, Trump has stoked a backlash. Deprived of any claim to a strong economy as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to rage, he is reduced to running again as an ethnic nationalist – akin to a “tribalist” in Africa.

In today’s America there are limits to blatant appeals to racial prejudice.

Trump absurdly claims to have done more for African-Americans than any president since Abraham Lincoln. But there are also political limits to how far Biden can go in embracing progressive calls for more rapid and complete integration.

The structural racism cited by the Black Lives Matter movement persists among liberals. But it does so as an implicit “racial contract” sustaining white privilege in access to housing, health care, education and employment. These are familiar issues in African countries, where a white tribal faction has historically dominated.

Sustainable democracy

In accepting the Democratic Party nomination, Biden focused on issues of character and leadership. He had Obama make the case for sustainable democracy and democratic inclusion. Obama pointedly referenced democracy 18 times in an address that reprised themes Africans heard in his 2018 Mandela Lecture in South Africa.

Trump, by contrast, did not reference democracy once in his unusually long 70-minute address accepting his party’s nomination for a second term.

Obama’s warnings to Americans that Trump threatens the integrity and sustainability of democratic institutions has a familiar ring. In his 2009 address to the Ghanaian parliament, he said:

Africa doesn’t need strongmen, it needs strong institutions.

Trump, along with his family, cronies and party enablers, appears to have achieved sufficient “state capture” to bring the US to a negative inflection point, as I predicted in 2018 (Chapter 10).

International relations

Of more immediate and practical concern to African nations is whether Trump’s nationalist unilateralism will continue to dominate US foreign policy. Or will there be a turn towards the multilateralism that Biden pledges to pursue? This includes:

-

restoring US funding and engagement in the World Health Organisation,

-

support for climate change mitigation,

-

immigration reform, and

-

support for collective security efforts to help Africans implement their commitments to ending armed conflicts.

African scholars also warn of a growing US-China “Cold War” under Trump. This would be detrimental to Africa.

Former US national security advisor and UN ambassador Susan Rice has called for an early summit with South Africa’s president and current African Union chair, Cyril Ramaphosa, should Biden be elected. Similarly, former US assistant secretary of state for Africa, Johnnie Carson, envisions a deepening of African-American partnerships under a Biden administration.

Electoral integrity

The threat to American democracy most familiar to Africans is an incumbent’s subversion of electoral integrity. Trump has repeatedly indicated his readiness to do something similar.

African electoral violence specialist Michelle Small has noted the need to compare Trump’s responses to racial protests with efforts to retain power by extra-constitutional means. All members of the African Union, despite democratic setbacks, are still obliged to hold periodic national elections, accessible to external observers.

Well documented interference in the 2016 and 2020 US elections by the Russian government, favouring Trump, may also portend similar risks of foreign manipulation of African elections.

What to expect

For African scholars and policymakers seeking to advance their national and regional interests in dealings with the US, the 59th presidential inauguration will also be an inflection point.

Should Trump prevail, there is unlikely to be any discernible change in his behaviour of the past four years. Occasional private disparagement of African nations and leaders will most likely continue.

There will be continued disengagement from initiatives of concern to Africans in public health, the environment, trade and other areas. His actions towards Africa, as in other areas, lack strategy. But he could still win.

Despite presidential neglect, programmes in public health, trade agriculture, health, education and young leaders launched by Trump’s predecessors would likely continue with bi-partisan Congressional support.

A Biden win offers a much richer field for contingency planning, although resources will be very constrained and attention will be overwhelmingly domestic.

That said, Biden would enter office owing a huge political debt to the support of African Americans. His ticket indicates receptiveness to honouring it, including immigration and other reforms affecting the African diaspora as well as expanding US-Africa partnerships. Planning to take advantage of those contingencies should be a priority in Africa.![]()

John J Stremlau, Honorary Professor of International Relations, University of the Witwatersrand. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.