How inequality is produced and reproduced generationally

- Paul Stewart and Edward Webster

The story of a working man who lived through apartheid – and his struggles after it ended.

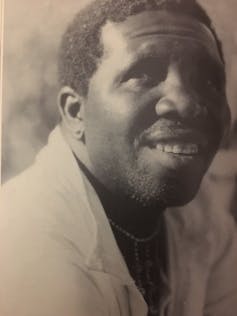

On 25 June, Mandlenkosi Makhoba, one of the last of a generation of grassroots worker leaders of the Federation of South African Trade Unions (Fosatu), was laid to rest above the majestic Mahlabathini plain in KwaZulu-Natal. He was 78.

Industrial workers such as Makhoba formed the basis of Fosatu, established in 1979 when democratic workers’ organisations forced the apartheid system to recognise their trade unions. This federation went on to win rights for black workers, contributed to a new workplace order and the establishment of national collective bargaining, while challenging racism and inequality in the workplace. It laid the basis for the formation of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) in 1985 with organised labour proving decisive in the transition to democracy.

Makhoba was, therefore, one of the “agents of change” who gave birth to South Africa’s modern labour movement. But he was not one of its beneficiaries. His death marks the passing of the era of the ‘labouring man’ – those industrial workers who were involved largely in manual labour, denied much formal education but stood for worker solidarity.

A working man’s life under apartheid

Makhoba’s life story illustrates the transition of established organised labour, from the voice of the dispossessed production worker struggling for recognition, to the relatively well protected suburban worker of today. He also represents the losers in the new South Africa, showing how inequality is consistently produced and reproduced. It tells the story of dreams lost and the need to recover the vision of a disappearing generation.

The stories of these working men and women has long been overshadowed by the big men and women of the successful struggle for democracy. Fortunately Makhoba lived to see the republication, in 2018, of his autobiography, The Story of One Tells the Struggle of All: Metalworkers under Apartheid. His story prefigures what has happened both locally and globally, namely how organised factory- and mine-based manual labour became sidelined by both advances in technology and the rise of neoliberalism.

We first met Makhoba, a foundry worker on the East Rand, now Ekhuruleni, nearly 40 years ago while researching the changing world of work in the metal industry. This archetypal, barrel-chested ‘labouring man’ poured molten metal to mould machine parts long before health and safety was taken seriously.

Alongside so many of his compatriots, he had migrated from his rural home in the “Bantustan” of KwaZulu to perform the toughest jobs that demanded physical strength and industrial discipline. “Bantustans” were the then mainly rural, undeveloped areas were black people were required to live under apartheid.

Seen as an unskilled “cast boy” under apartheid, Makhoba was paid considerably less than the white “supervisors” he had trained. “That made me angry,” he said at the time.

I don’t get the money he is getting, but I am supposed to be his teacher! How can a clever man be taught by a stupid man like myself?

Throughout his working life Makhoba oscillated between town and countryside. He lived in the sprawling single sex hostel complex for black male migrant workers in Vosloorus, to the east of Johannesburg, a bus drive from his workplace. He was deeply dissatisfied with the filthy conditions in the hostel and the lack of privacy, with 16 men to a room and not much better than the mine compounds and concrete bunks these hostels had replaced. Men had to cook after a long day’s work and travel. Theft was rife and excessive drinking and violent assaults marked the weekends.

Accompanying this sense of deprivation was the resigned acceptance of being unable to live a normal social life. Of greatest concern for Makhoba was going home to Mahlabathini, only to find the decline of parental authority. This affected him deeply.

When a man comes home there is no respect for him anymore, because he has been away from home for such a long time.

The union

It is not surprising then that in July 1979 Makhoba joined a fledgling metal union at the time, later to become the National Union of Metal Workers of South Africa. He said:

I joined the union because workers are not treated like human beings by management, but like animals.

The men who joined the union came from similar districts in KwaZulu and elsewhere and shared the rigours of hostel life. They were, in other words, rooted in networks of mutual support.

Although Makhoba had been working in the city intermittently for 20 years when we first met him, his cultural world was shaped by his rural values:

I work here, but my spirit is in Mahlabathini. My spirit is there because I come from the countryside. I was born there and my father was born there.

In 1983 he was dismissed from the foundry for participating in an illegal strike. Following episodic periods of temporary employment, he returned home permanently.

Deprivations of rural life

In 1991 we tracked him down to his homestead on a mountain top in Mahlabathini. He had acquired 15 head of cattle, ten from the ilobolo (bride price) of his two oldest daughters.

Fifteen people – his wife and 14 children – lived with him in the six rondavels of his neatly swept homestead where he had access to land on which he grew maize and some vegetables.

But a closer examination of this household revealed a sad reality: Mandlenkosi’s home was a picturesque version of a rural slum. The children spent their days doing household chores, chopping firewood and collecting water twice daily from the local stream half a kilometre away. Their diet, except on special occasions, was confined to mealie meal and they often faced hunger.

As the children matured and moved away, Makhoba suffered increasingly poor health. Unable to continue working at a local store, the lack of food intensified. As he drifted into the long autumn of his life, suffering with Parkinson’s disease, the family had become too poor to farm their land. The hopes of yesteryear, of a new start and a new, better society, had become “a dream”.

The inequality in life-chances that shaped Mandlenkosi’s life continues as his children are part of the growing millions of marginalised workers eking out an existence in the rural slums and informal settlements of our urban areas.

Meanwhile, today Cosatu is largely a home for relatively privileged public sector workers, a third of whom have post high school qualifications and 40% have professional jobs. Production in the foundry where Makhoba once worked is now largely robotised.

With many of the manual jobs disappearing, it is farewell to the traditional labouring man as the precarious worker of the digital age is ushered in.![]()

Paul Stewart, Associate Professor in Sociology, University of Zululand and Edward Webster, Distinguished Reserach Professor, Southern Centre for Inequality Studies, University of the Witwatersrand. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.