Journalism of Drum’s heyday remains cause for celebration – 70 years later

- Lesley Cowling

The magazine grew to be the largest circulation publication for black readers in South Africa, and expanded to include East and West African editions.

Drum becomes an online-only magazine this month, almost 70 years after it was first launched as an African print publication.

The magazine is now a celebrity-focused human interest magazine. But it played a very different role in the 1950s and 1960s, when it is widely considered to have created new possibilities for identity for black South Africans. It was also crucial to the development of South African literature.

“The Drum boys”, a group of young writers employed by the magazine in its early years, served an emerging urban black readership in the first decade of apartheid, which came into force in 1948. Their lively chronicles of urban adventures made them popular characters, as well as contributing to Drum’s commercial success.

The magazine grew to be the largest circulation publication for black readers in South Africa, and expanded to include East and West African editions.

The “Drum era” of the 1950s has been romanticised as “the fabulous decade” through posters, photographs, film and exhibitions. The Drum look has found its way into fashion (T-shirts printed with Drum covers), décor and television, commercials and game shows such as Strictly Come Dancing.

Despite the nostalgia, many South Africans are not familiar with the journalism of early Drum. But magazines, as media academic Tim Holmes notes, are crucial to the construction of identities because of their intense focus on readers and reader communities.

Such journalism, despite its lightweight appearance, tells us complex stories about culture. Magazines also provide a space for creative forms of journalism.

Through their use of storytelling, personal narrative, local lingo and vivid scenes of everyday life, the Drum writers engaged in an ongoing construction of cosmopolitan identity for Johannesburg city dwellers. Literature scholar Michael Titlestad has called this process “improvisation”, comparing the writing in Drum with the improvisation in local jazz that took place in the 1950s.

The beginning

While countries throughout Africa were heading to independence in the 1950s, in South Africa the National Party was introducing draconian apartheid laws. There was also increased migration to cities. Africans could not own property, but were able to obtain freehold rights in certain areas, such as Sophiatown, on the outskirts of Johannesburg.

Sophiatown was a place where people could mingle across the colour bar. Its shebeens (informal taverns), music, celebrities and gangsters were the source of many Drum stories.

The African Drum was launched in 1951. After a lacklustre three months, the owner, Jim Bailey, brought a friend out from England, Anthony Sampson, to edit the magazine. They did some informal research and were told that black readers wanted sport, jazz, celebrities and “hot dames”.

“Tell us what’s happening right here, man, on the Reef!”

Henry Nxumalo, an ex-serviceman with some experience as a journalist, was highly influential in developing Drum’s style as the magazine sought to attract black readers. Writers came from diverse backgrounds.

Todd Matshikiza was a musician (and went on to compose the musical King Kong). Can Themba, a teacher, won a fiction contest held by the magazine in 1952. Arthur Maimane was a schoolboy from St Peter’s Secondary School in Sophiatown with a passion for American crime writing. A young German, Jürgen Schadeberg, took the pictures, later joined by Bob Gosani and Peter Magubane.

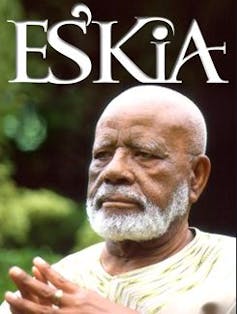

As the magazine’s circulation grew, now iconic names in South African literature joined. These included Casey Motsisi, Bloke Modisane, Es’kia Mphahlele, Lewis Nkosi and Nat Nakasa.

Mostly without journalism training, the Drum writers began experimenting with tales of everyday life in the black townships. Nxumalo and Matshikiza, as the earliest writers on Drum, were influential in creating inventiveness in both reporting and writing.

Matshikiza developed a lively style to write about jazz, which was dubbed “Matshikese”. He was described as hammering on his typewriter like a musician playing a keyboard.

Maimane wrote serialised fiction in the mode of American hard-boiled detective stories. Others recounted first-person adventures in the shebeens and clubs, wrote confessional stories on behalf of characters they interviewed, or offered their own opinions.

In their stories, they used the styles of fiction writing more than news reporting, as many of the Drum writers also wrote short stories and novels. As John Matshikiza, Todd’s son, noted years later in the preface to a collection of Drum articles:

The startling thing is that there is no real dividing line between the two styles of writing: the journalistic and the fictional.

Investigative journalism

At first, circulation was slow to pick up. Then Nxumalo pitched a story about the abuse of labourers on the farms of Bethal. Nxumalo and photographer Schadeberg posed as a visiting journalist and his servant to gain access to the farms. The magazine published an eight-page article outlining the abuses, bylined “Mr Drum”.

The edition sold out, and public response reached Parliament.

After this, Drum carried regular investigations, mostly driven by Nxumalo. He got himself arrested so that he could write about prison conditions and took a job at a farm where a worker had been killed. “Mr Drum” became a celebrity, and his feats of investigative journalism have rarely been matched in South Africa.

Drum sales hit 73,657 in 1955, making it the largest circulation magazine in Africa in any language. The devil-may-care spirit of the Drum writers, however, was difficult to sustain as the apartheid structures bore down on them.

By 1956, Sophiatown’s black residents were being removed, to make way for an exclusively white suburb, in line with the apartheid policies that prohibited the mixing of “races”.

In December 1956, Nxumalo was stabbed to death while out on an investigation. His death deeply affected his fellow writers.

The increasing repression of the 1960s destroyed the journalists of the “Drum school”. Most went into exile. Drum was banned and stopped publishing for some years. The title was eventually revived, and sold in 1984 to Nasionale Pers, an Afrikaans media company with close ties to the apartheid government.

The 1980s

In the 1980s, many of the early Drum writers were unbanned, releasing their writing back into South Africa’s public domain. Mike Nicol, who wrote a book on 1950s Drum, describes the impact of this moment as history shifting beneath one’s feet, revealing a “lost country”. There was surge of interest by literature scholars. Michael Chapman, in the 1980s, argued that

the stories in Drum mark the substantial beginning, in South Africa, of the modern black short story.

Lewis Nkosi, on the other hand, regretted the short-lived potential of the Drum generation and the production of what he called “journalism of an insubstantial kind”.

Mphahlele felt that Drum did not deal seriously with social issues. Others argued that Drum was not explicitly committed to the liberation struggle.

Many scholars argue that the Drum writers, in detailing everyday experience, showed quite powerfully the violent impact of the apartheid system on black South Africans. Nkosi noted:

No newspaper report … could ever convey significantly the deep sense of entrapment that the black people experience under apartheid rule.

Their inventive style of using fictional tactics to tell non-fiction stories pre-dated the New Journalism of America – touted by Tom Wolfe as a brand new approach to journalism – by a decade.

This edited extract is adapted from Echoes of an African Drum: The Lost Literary Journalism of 1950s South Africa, in Literary Journalism Studies.![]()

Lesley Cowling, Associate Professor in the Department of Journalism, University of the Witwatersrand. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.