Ancient southern African rock engravings finally find a fitting home

- Tammy Hodgskiss and Amanda Esterhuysen

The Origin Centre has added a new wing that's perfect for a visit, the Rock Engraving Archive.

The Origins Centre housed on the campus of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg has just opened a new Rock Engraving Archive to the public. This is the biggest collection of rock engravings on display on the continent. It is the culmination of decades of shifting policy – and perceptions – of how South Africa should curate its rock art heritage. The exhibition marks a coming home of these extraordinary rocks that it’s now recognised should never have been removed from their natural environment.

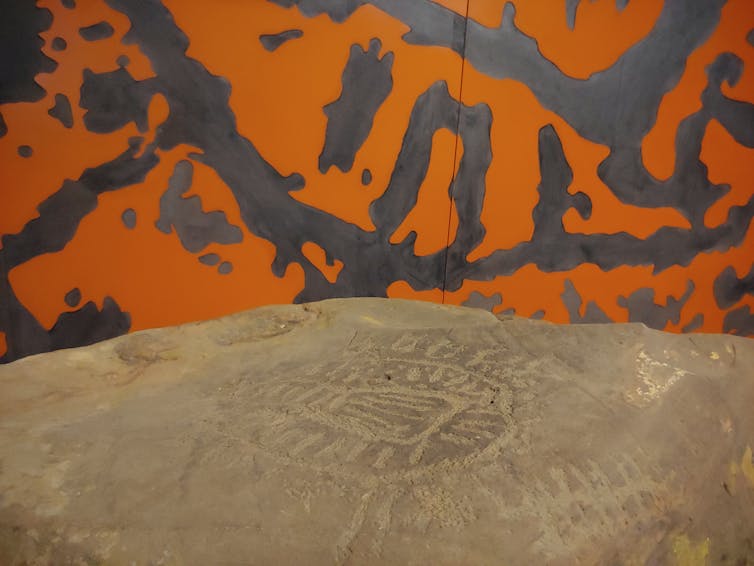

The archive contains 76 boulders engraved with intricate images. The engravings depict animals (both realistic and mythological or zoomorphic) and geometric designs. Some have depictions of wagons or text.

Most of the engravings of animals may have been created by San hunter-gatherers, or their ancestors who were among the first people of southern Africa. There is an ongoing debate about whether the geometric images mark the arrival and movement of the Khoi or Khoekhoen stock-herding people. The geometrics may represent the spread and change of ideas among the San and a change in their hunter-gatherer way of life.

The majority of the engravings are on hard dolerite rocks. The mains techniques used to engrave the rocks are pecking or fine-lines, where the markings are made with a sharp object (such as a harder, denser rock or metal).

Some of the engravings can only be seen with lighting at a certain angle, as would have been the case when they were in their place of origin in the landscape – at certain times of day, and in certain light, the engravings would have ‘magically’ appeared. The sound that some rocks made when struck would have added to the experience on an auditory level, and a mark would have been left with each strike. Marks from the sharpening of tools and weapons against the hard surfaces also add a layer of meaning to the rocks.

There are other non-human traces to be found on some of the rock surfaces. Marks made by the repeated rubbing of animals against the rock surface, or through wind and water erosion.

The epic journey of the rocks

Today, every effort is made to conserve rock engravings in their original context. But in the first half of the 1900s many painted and engraved panels were removed to museum collections. At the time it was believed that this was the best way to protect them.

In the 1960s Wits University’s Dr Emil Paul Friede and Prof Revil Mason from the South African Archaeological Society assembled a major collection of rock engravings that had been removed from their original locations. The rocks had come from the Magaliesberg and around the Klerksdorp and Schweizer-Reneke region of the North West Province.

The engravings were arranged for exhibition to the public in a special display in the Johannesburg Zoological Gardens (now the Johannesburg Zoo). This was officially opened on 5 September 1970 as the Museum of South African Rock Art.

However, the exhibit was difficult to maintain, and staff and public grew increasingly uncomfortable about the social implications of displaying indigenous art in a zoo.

In the early 1990s the rock engraving exhibit was closed. The smaller pieces were taken to Museum Africa, but 36 larger pieces were left on display at the zoo. Over time the rock engravings at the zoo were neglected and became covered in moss.

In May 2000 the boulders were removed to Wits University under the curation of the Rock Art Research Institute, with funding from the Department of Arts and Culture.

Between 2000 and 2004 a team of conservators worked on cleaning, conserving and restoring these engravings. The engraved boulders housed in Museum Africa were moved to Wits University in 2005.

In 2017 these boulders were moved to the Origins Centre’s new wing and in 2019 the archive was opened to the public. The completion of the archive was funded by the National Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences.

The stories that the engravings tell

The first debates and publications about South African rock art centred on who made the rock art and why. Most incorrectly attributing the art to foreigners. While these early interpretations were entirely untrue, the interest in rock art raised an awareness about the need to protect it from damage and destruction. This led to South Africa’s first heritage legislation – the Bushman-Relic Protection Act of 1911 – which protected rock art, artefacts, and burials, and controlled the export of material to foreign museums.

Until the 1980s little attention was given to recording the original context of the rock engravings. This changed when researchers began to appreciate how the engravings interacted with the landscape – how the experience of the art transforms with the light, wind, rain, sounds and the perspective of the viewer. Many of the meanings of the engravings may be unknown to us but the stories and beliefs of numerous individuals have been carefully engraved on these boulders.

The Origins Centre Rock Engraving Archive is the largest archive of rock engravings in the country. With the Rock Art Research Institute, it aims to facilitate the collection and organising of information and interpretations about these displaced pieces of art.

These national treasures are now a permanent component of the Origins Centre Museum experience – go and explore it for yourself.![]()

Tammy Hodgskiss, Curator at the Origins Centre Museum, University of the Witwatersrand and Amanda Esterhuysen, Associate professor School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, University of the Witwatersrand. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.