Did a large meteorite hit the earth 12,800 years ago? Here’s new evidence

- Francis Thackeray

Could platinum-rich dust associated with the impact of a very large meteorite have contributed to major climatic change and extinctions 12,800 years ago?

Just less than 13,000 years ago, the climate cooled for a short while in many parts of the world, especially in the northern hemisphere. We know this because of what has been found in ice cores drilled in Greenland, as well as from oceans around the world.

Grains of pollen from various plants can also tell us about this cooler period, which people who study climate prehistory call the Younger Dryas and which interrupted a warming trend after the last Ice Age. The term gets its name from a wildflower, Dryas octopetala. It can tolerate cold conditions and was common in parts of Europe 12,800 years ago. At about this time a number of animals became extinct. These included mammoths in Europe, large bison in North America, and giant sloths in South America.

The cause of this cooling event has been debated a great deal. One possibility, for instance, is that it relates to changes in oceanic circulation systems. In 2007 Richard Firestone and other American scientists presented a new hypothesis: that the cause was a cosmic impact like an asteroid or comet. The impact could have injected a lot of dust into the air, which might have reduced the amount of sunlight getting through the earth’s atmosphere. This might have affected plant growth and animals in the food chain.

Research we have just had published sheds new light on this Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis. We focus on what platinum can tell us about it.

How platinum fits into the picture

Platinum is known to be concentrated in meteorites, so when a lot of it is found in one place at one time, it could be a sign of a cosmic impact. Platinum spikes have been discovered in an ice core in Greenland as well as in areas as far apart as Europe, Western Asia, North America and even Patagonia in South America. These spikes all date to the same period of time.

Until now, there has been no such evidence from Africa. But working with two colleagues, Professor Louis Scott (University of the Free State) and Philip Pieterse (University of Johannesburg), I believe there is evidence from South Africa’s Limpopo province that partly supports the controversial Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis.

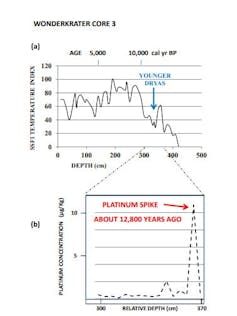

The new information has been obtained from Wonderkrater, an archaeological site with peat deposits at a spring situated outside a small town to the north of Pretoria. In a sample of peat we have identified a platinum spike that could at least potentially be related to dust associated with a meteorite impact somewhere on earth 12,800 years ago.

The platinum spike at Wonderkrater is in marked contrast to almost constantly low (near-zero) concentrations of this element in adjacent levels. Subsequent to that platinum spike, pollen grains indicate a drop in temperature. These discoveries are entirely consistent with the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis.

Wonderkrater is the first site in Africa where a Younger Dryas platinum spike has been detected, supplementing evidence from southern Chile, in addition to platinum spikes at 28 sites in the northern hemisphere.

We are now asking a question which needs to be taken seriously: surely platinum-rich dust associated with the impact of a very large meteorite may have contributed to some extent to major climatic change and extinctions?

A meteorite crater in Greenland

Very recently a large meteorite crater with a diameter of 31km was discovered in northern Greenland, beneath the ice of the Hiawatha glacier. It is not certain that it dates to the time of the Younger Dryas, but the crater rim is fresh, and ice older than 12,800 years is missing.

It seems possible (but is not yet certain) that this particular crater relates to the hypothesised meteorite that struck the earth at the time of the Younger Dryas, with global consequences.

The effects of a meteorite impact may potentially have contributed to extinctions in many regions of the world. There is no doubt that platinum spikes in North America coincide closely with the extinction of animals on a big scale about 12,800 years ago.

Extinctions in Africa

In a South African context, my team is suggesting that platinum-rich cosmic dust and its associated environmental effects may have contributed to the extinction of large animals that ate grass. These have been documented at places such as Boomplaas near the Cango Caves in South Africa’s southern Cape, where important excavations have been undertaken.

At least three species went extinct in the African subcontinent. These included a giant buffalo (Syncerus antiquus), a large zebra (Equus capensis) and a large wildebeest (Megalotragus priscus). Each weighed about 500kg more than its modern counterpart.

There may have been more than one cause of these extinctions. Hunting by humans could have been a factor. And the large buffalo, zebra and wildebeest had already been affected by habitat changes at the end of the last Ice Age, which was at its coldest about 18,000 years ago.

What about human populations? A cosmic impact could have indirectly affected people as a result of local changes in environment and the availability of food resources, associated with sudden climate change. Stone tools relate to the cultural identity of people who lived in the past. Around 12,800 years ago in at least some parts of South Africa there is evidence of an apparently abrupt termination of the “Robberg” technology represented by stone tools found for example at Boomplaas Cave.

Coincidentally, North American archaeological sites indicate the sudden end of a stone tool technology called Clovis.

But it is too early to say whether these cultural changes relate to a common causal factor.

Reality check

The Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis, and the evidence to support it, is a reminder of how much can change when a rocky object hits the earth. Many asteroids are situated between Mars and Jupiter, and on occasion some come very close to our planet. The probability of a large one striking earth may seem to be low. But it’s not impossible.

Take Apophis 99942. It is classified as a potentially hazardous asteroid. It is 340 metres wide and will come exceptionally close to the earth (in relation to an Astronomical Unit, the distance between us and the sun) on Friday April 13 2029. The probability of its hitting us in ten years’ time is only one in 100,000. But the probability of an impact may be even higher at some time in the remote future.

What’s more, comets associated with the Taurid Complex approach the earth relatively closely at intervals of centuries. So a large asteroid or comet could fall to earth in the foreseeable future.

The Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis is highly controversial. But the evidence suggests it is not improbable that a large meteorite struck the earth as recently as 12,800 years ago, with widespread consequences.![]()

Francis Thackeray, Honorary Research Associate, Evolutionary Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.