South Africa’s black middle class is battling to find a political home

- David Everatt

South Africa’s black middle class is growing numerically – and growing politically restive.

But does it see the world differently from others? Does this translate into voting behaviour?

These questions require close consideration because the black middle class is already a critical constituency in some of the country’s wealthier provinces such as Gauteng, and is looking for a political home that’s stable and serves its class interests.

The post-apartheid project was meant to unlock the economic energies of all South Africans. But sluggish economic performance, coupled with a decade of state capture and the scorn former President Jacob Zuma felt towards “clever blacks”, has left the black middle class angry and wary.

They are angry at their exclusion from mainstream economic activity, where “boardroom racism” and a racial ceiling are clearly at work. And they are wary that unless they are members of the governing African National Congress (ANC’s) “charmed circle”, their chances of accessing state funds – normally required to help grow and stabilise the indigenous bourgeoisie after liberation – are at best slender.

A recent survey conducted for the ANC and which the party has not released publicly, asked over 3 000 Gauteng voters a range of questions about attitudes to politics past and present. The survey showed that there are stresses and strains in the body politic in general, many of which are most acutely felt by the black middle class.

As a young man from Johannesburg put it in a focus group:

The one thing that is changing that is killing the ANC is the individuals inside. There literally is a clique, if you belong to this clique within the party, you will be all right and if you are against any of their ideas, you are pushed to the side.

The implications for the ruling party are clear: if its policy of appointing party loyalists to government positions (cadre deployment and state capture (or even overt patronage) remain the order of the day, the black middle class will simply withdraw all support from the ANC. This would be a dire indictment of the ruling party.

Definition challenges

Many academics, correctly, spend a lot of time worrying about the precision of various definitions of (middle) class. These range from occupation to income and education to consumption, through to subjective self-identification. They also correctly bemoan the clumsiness of survey attempts to measure class in all its nuances.

While accepting the weaknesses of most definitions, we nonetheless need to develop and use what we can to try to understand if such a class exists, and what its political behaviour might be.

In this case, we started with a household income in excess of R11 000 a month. This is scarcely a princely income, but analysed in the context of “black African” income generally, it certainly includes the “middle stata”.

To make the definition more nuanced we included those who self-identified as upper-middle class (or, in less than 2% of cases, “upper class”).

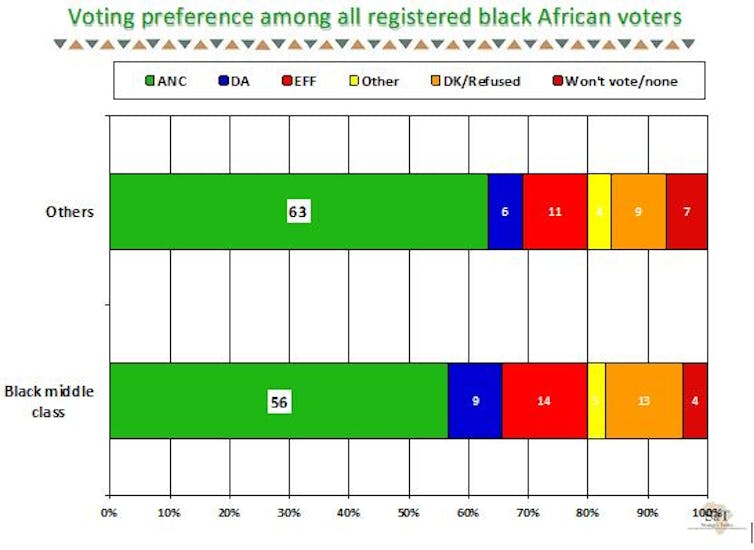

As the voting intention graphic below shows, even with this rough and ready definition, there seem to be different political dynamics at play for the black middle class.

Voting patterns

The graph makes a number of key issues clear. Firstly, the ANC has held – or regained - the loyalty of the majority of black middle class Gautengers, but only just. Where 63% of non-middle class black Africans in Gauteng (who were registered to vote) told us they will vote ANC, this dropped to 56% among the black middle class. Their loyalty is remarkable, given the past decade.

Part of the reason is the state of the Democratic Alliance (DA), the leading opposition party. The DA should be the natural home for an emergent and ambitious middle class, with its talk of equal opportunities, its general dislike of cadre deployment and its strident attacks on ANC corruption. However, the DA is deeply divided - over race.

The DA committed policy seppuku as the election approached, with its members and commentators freely attacking party leader Mmusi Maimane over the issue for fear of alienating their traditional, rather tribal, white voter base. Any mention of race, or redress, or race-based inequality, it seems, was to be banished - while asking those at the receiving end of racism to vote DA.

The signal to black middle class South Africans was clear: fears that the DA remained a “white” party, or a party in hock to white interests, remained; and they were unlikely to be terribly welcome. This remarkable pre-election behaviour split the uneasy alliance of those previously opposed to Zuma and everything he and the ANC represented before Cyril Ramaphosa became the party leader. It seems to have driven those who dipped their toes in DA waters back to the ANC fold, or into the arms of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) or - for a significant number - into the political wilderness.

The ANC has never been able to sustain a strong appeal to higher educated or higher income voters. The DA has now fallen back dramatically in these areas, and the graphic makes it clear that the EFF hold more appeal to black middle class voters than the DA. Whether this is because of their strident opposition to racism, or is done to fire warning salvos across the bows of both ANC and DA, the result is that the DA and EFF are fighting for the same small portion of black middle class votes - which are unavailable to the ANC - albeit from vastly different ideological positions.

The ANC continues to enjoy the lion’s share of black middle class votes from those willing to vote. But for how long?

The apathy

While 67% of black middle class voters do intend to vote, a third will stay at home on 8 May, cursing all political parties for failing to represent their interests, according to the survey. Chunks of the black middle class may vote, but far from enthusiastically. And a great many will not vote.

Among those who said they would vote, according to our survey results, 17% “don’t know” (or won’t tell) who they will vote for – even though many had previously overcome their unhappiness at the perceived “whiteness” of the DA:

And, as commentator Nkateko Mabasa puts it,

although most black South Africans will continue to regard the DA as a white party … there is a growing number of black middle-class liberals who are tired of being ashamed for being regarded as “coconuts” [black on the outside, white on the inside].

Maimane was a very powerful magnet for black middle class voters, but as his party rounded on him over race, white privilege and the need to maintain the white vote, Ramaphosa has inevitably exerted his own magnetic pull. He is charismatic and emblematic of what the black middle class can achieve. It is therefore no surprise that DA support in this key segment has all but evaporated.

Those who will never forgive the ANC its past sins are either opting out or voting EFF. The question for the future is whether any current party can reflect the needs and aspirations of the black middle class - who, importantly, are black as well as middle class - or whether they represent the social base of some not-yet formed political party.![]()

David Everatt, Head of Wits School of Governance, University of the Witwatersrand. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.