Kewpie: understanding what it meant to be queer in District Six under apartheid

- Haley McEwen

Across many parts of Africa homosexuality is often referred to as “unAfrican” - a western imposition that will undermine a traditional African.

It has also been described as “unnatural” and “ungodly”.

These narratives are subverted in an exhibition currently on display at the District Six Homecoming Centre in Cape Town. “Kewpie: Daughter of District Six” does this through a compelling, and thoughtfully curated, installation consisting mainly of photographs.

The exhibition shows that queer people occupied an important place in Cape Town’s District Six – one of the most celebrated communities in South Africa. The 60 000 residents of District Six were evicted, and their homes demolished, by the apartheid government when the area was declared “whites only” in 1966. All were forced to move to racially segregated residential areas across the Cape Flats.

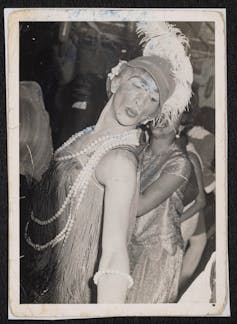

The exhibition celebrates the life of Kewpie, a drag artist and hairdresser who came to be widely known and loved in the community of District Six where she lived for many years. She was born in 1942, six years before apartheid was formally established, and died in 2012.

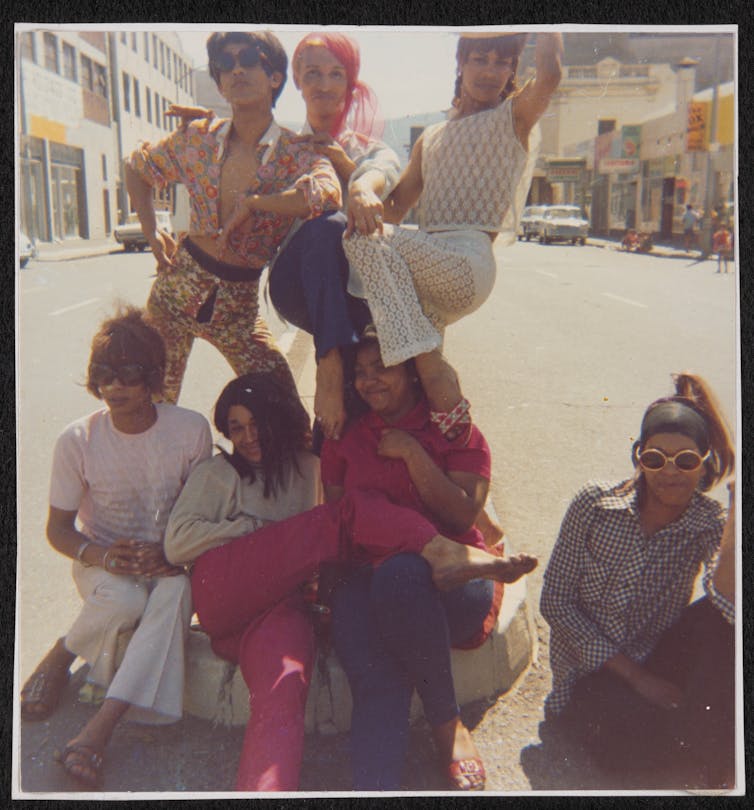

Kewpie kept a thorough archive of photographs that had been taken of her and her friends. She personally labelled the photographs. In 1999 she transferred her collection to Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA), a queer archive based in Johannesburg.

The exhibition was co-curated by Jenny Marsden, a researcher based at Gay and Lesbian Archive (GALA), and Tina Smith, curator of the District Six Homecoming Centre. I was fortunate to be a part of Kewpie’s dream – this exhibition – becoming a reality. The Wits Centre for Diversity Studies, where I am based, co-hosted a walkabout and dialogue with GALA and the District Six Homecoming Centre. It provided a space for reflection on the exhibition and the queer histories of District Six that it portrays.

From the exhibition, one understands that Kewpie’s gender identity was fluid. Kewpie didn’t strictly identify as either male or female, but she and her friends typically used feminine pronouns (she/her) to refer to one another, and referred to one another as sisters.

Bulldozing of the community

The exhibition provided a space where queer residents of District Six, and the community of former residents more broadly, could gather to celebrate one of its icons. The events that accompanied its opening also brought together different generations of queer people of various racial, ethnic and religious backgrounds.

It’s easy to become seduced by the photographs of Kewpie’s spectacular life, with its feathers, incredible outfits and the recreated salon installation including wigs styled for the times. But, to fully process the significance of Kewpie’s public persona, drag performances and everyday work at the salon, it is necessary to remember that life for the people of District Six was never easy. Its queer residents faced oppression and violence, both inside and outside of the community.

Established in 1867 for freed slaves, merchants, artisans, labourers and immigrants, District Six’s residents had already experienced generations of oppression by Dutch and British colonial governments before their community was destroyed by the apartheid regime. Recognition of this history enables one to fully grasp the oppressive legacies that Kewpie and her friends subverted through their everyday practices.

They were celebrated and integrated into the community. But they also experienced oppression and exclusion on account of their gender expression and sexual orientation.

Exclusion

At the dialogue that took place following the exhibition opening, queer former residents spoke of their experiences of being excluded on the basis of their sexuality.

Leigh Davids of Sistazhood (an activist organisation for transgender women sex workers), spoke about the forms of exclusion that transgender women and gender non-conforming people of colour continue to experience in Cape Town. Sex workers in particular and homeless lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer (LGBTIQ) people experience harassment from the police and evictions from sleeping in public areas. These current realities speak about the pain and exclusion that Kewpie and her community experienced throughout her life and that so many continue to experience daily.

Kewpie was “out” in the community of District Six where she was celebrated as the “daughter” of the community. However, her identity as a transgender woman, and her intimacy with men, was criminalised by the apartheid government and the colonial British system preceding it. Although Kewpie did not identify as a gay man, homosexual sex was considered an aberration within the Calvinist belief system that informed Afrikaner Nationalism.

The exhibition brings queer history into the foreground within stories that are told about the past. Providing a queer lens through which District Six is remembered in the exhibition, the collection of photographs depicting Kewpie’s life centre queer experiences of colonial oppression. In remembering apartheid and the years leading up to forced removals in ways never seen before, these histories awaken new understandings about the role and position of queer communities then and now.

With the end of apartheid, policies that had policed gender and sexuality were formally dismantled. Same-sex and interracial intimacy and partnership were un-banned. Policies that discriminated against women were removed. Liberation from apartheid was intended to mean liberation for all, including women and LGBTIQ identifying people.

Gender non-conforming and queer people continue to face discrimination in all social spheres. For LGBTIQ people from communities historically oppressed by colonialism and apartheid, the experiences of exclusion and marginalisation are compounded by still ongoing systems of racialised oppression.

This article was written with input from the Gay and Lesbian Archive (GALA).![]()

Haley McEwen, Research Coordinator, University of the Witwatersrand. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.