Lessons about history by Twitter: two South Africans go head-to-head on slavery

- Roger Southall

A recent exchange on Twitter between South African TV personality Sizwe Dhlomo and Western Cape Premier Helen Zille, is worthy of close examination.

Because it raises important questions about how history is viewed, how debates unfold on social media and how South Africans deal with racism and diversity.

Initially, Dhlomo basically baited Zille by redirecting a tweet by the King Centre – an advocacy group set up in memory of Martin Luther King – which issued a blunt proclamation that:

There was nothing righteous, just or positive about the Transatlantic slave trade or slavery in America. Nothing.

Zille replied:

I agree, there was absolutely nothing positive about slavery or the slave trade. If you read the transformed (South African) history textbook… you will see the acknowledgement that despite its many evils, colonialism helped end slavery in parts of Africa.

Dhlomo then responded:

You, like it or not, are a beneficiary of colonialism, albeit indirectly. Your biases, whether you’re aware of them or not, make it unlikely for you to be able to accurately weigh up the negatives of colonialism versus the positives you speak of.

After asserting that the motive of colonialism was never to ultimately benefit the colonised (an assertion with which Zille agreed), he rounded off by posing the question whether or not there might have been alternative historical alternatives to colonialism:

Without colonialism, were the colonised nations doing well? Would they have continued to do so and develop at their own pace?

before providing his own answer:

I see no reason why the answer would be no.

Four points can usefully be made about all this. The first is about the limitations, and dangers, of engaging in serious debates on Twitter; the second is that reducing history to simple matters of right or wrong is fraught with risk; thirdly, the need to recognise that history can be contradictory; and finally that history, is and always has been, contested.

The inappropriateness of Twitter

Twitter is inappropriate for complex historical debates. There is just too much to be said in defence of any position – whether conservative, liberal or radical – for it to be reduced to exchanges of 280 characters or less. The process of assessing the motivations, dynamics and impacts of colonialism by scholars is both constant and continuous, and reducing historians’ debates to trite summaries is dangerous.

This is not to say that the history should be the property of only the historians, and that ordinary people should keep out. History is, after all, actually as much about the present as the past. But we should beware of the misuse of history for political point-scoring.

Yet if Dhlomo may be considered as guilty of this, Zille has only herself to blame for setting herself up as a target by her initial ill-advised tweet on colonialism sent more than a year ago while she was in Singapore.

Just as Twitter can’t encompass the complexity of historical debate, reducing history to matters of simply right or wrong, or good or bad, is similarly fraught with risks. This was gloriously and famously illustrated by 1066 and All That, by WC Sellar and RJ Yeatman, published as long ago as 1930, which reduced English history to a hilarious parody of good and bad kings and queens.

The fundamental point is: history is almost always contradictory, moving in different directions at the same time.

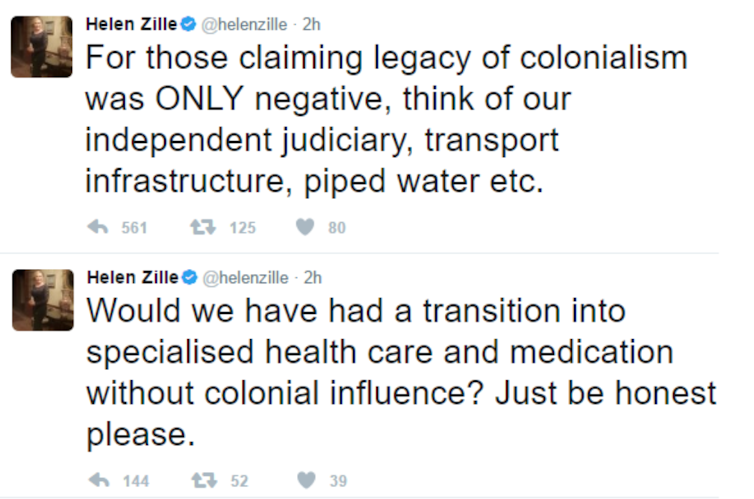

It would seem that this is the major point that Zille wants to make in her various tweets and more extended comments about colonialism. She will claim that she is not defending colonialism, and the racism inherent in it, but pointing out that, like God, it moves in a mysterious way.

In her defence, we might reference debates about the origins of the “developmental state” in Southern Africa. Broadly, a number of radical scholars (by that I mean not conservative ones) have explored how settler colonialism fostered capitalism development. Examples include Bill Freund’s “SA Developmental State of the 1940s”.

In South Africa, for example, the launch of parastatals – such as the power utility Eskom in the 1920s – fostered rapid growth and the creation of an Afrikaner bourgeoisie. In Marxian terminology, state policies helped develop the forces of production – but only for the benefit of white people in general, and Afrikaners in particular.

Would South Africa have industrialised as fast, or in a more beneficial way, without such a white-driven developmental state – as Dhlomo implies? Frankly, we don’t know. Nonetheless, we must allow that counter-factual history, the exploring of possible alternative historical paths that might have been followed if A and B had not happened, is a legitimate line of enquiry. Yet it can never be a substitute for exploring what did happen.

History is always contested

While Zille should not be pilloried for indicating that history is contradictory, she needs to be far less slapdash in lauding what she perceives as the benefits of colonialism. Her exchange with Dhlomo on slavery offers a prime example.

Let’s not be so politically correct that we have to deny the fundamental truth of Zille’s proposition that the colonial intervention involved the attempted abolition as well as the promotion of slavery. However, the problem is not what she says but what she does not say. We need to ask, for instance, why and how the British chose to bring slavery to an end.

The “why” must necessarily refer to the heroic labours of the anti-slavery movement of the day. But it also needs to be pointed out that abolition featured slave-owners being compensated by the state, whereas the slaves themselves received nothing.

In addition, much of the compensation was redirected into investment in the then rapidly expanding railway system in Britain, thereby providing a direct boost to the development of capitalism and colonialism.

We might also want to remember that when the American Civil War broke out, Britain initially supported the South, as it wanted to avoid the disruption of slave-produced cotton to its textile mills in northern England.

In short, it’s all so much more complicated than any attempt to produce a historical balance sheet in which the good of colonialism may outweigh, or at least compensate for, some of its negative impacts. Historians of whatever stripe, and certainly not politicians, cannot be allowed to omit inconvenient facts.

Yet while Dhlomo may be granted as much space as he likes to explore and condemn the brutalities of slavery and colonialism, he cannot be allowed to argue, as he did, that Zille’s historical judgement is inherently flawed by the inherent biases which flow from her being “a beneficiary of colonialism, albeit indirectly”.

This is dangerous nonsense. For a start, it assumes there is such a thing as “correct” history. There is not. History is always contested.

More saliently, Dhlomo’s assertion is absurdly deterministic, implying that social background (in today’s South Africa, read “race”) dictates the capacity to “understand” history. This is rubbish. True, it is very likely that the social experiences of being black will provide some major comprehension of colonialism. But it does not follow that being white necessarily blocks such understanding.

![]() If it did, then Marx’s thoughts on colonialism should themselves be deleted from the black reading list.

If it did, then Marx’s thoughts on colonialism should themselves be deleted from the black reading list.

Roger Southall, Professor of Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.