How we recreated a lost African city with laser technology

- Karim Sadr

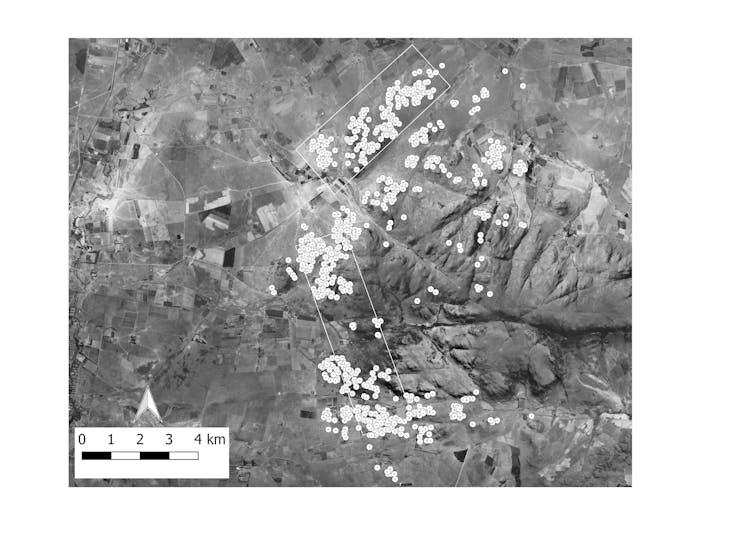

LiDAR, was used to “redraw” the remains of the city, along the lower western slopes of the Suikerbosrand hills near Johannesburg.

There are lost cities all over the world. Some, like the remains of Mayan cities hidden beneath a thick canopy of rainforest in Mesoamerica, are found with the help of laser lights.

Now the same technology which located those Mayan cities has been used to rediscover a southern African city that was occupied from the 15th century until about 200 years ago. This technology, called LiDAR, was used to “redraw” the remains of the city, along the lower western slopes of the Suikerbosrand hills near Johannesburg.

It is one of several large settlements occupied by Tswana-speakers that dotted the northern parts of South Africa for generations before the first European travellers encountered them in the early years of the nineteenth century. In the 1820s all these Tswana city states collapsed in what became known as the Difeqane civil wars. Some had never been documented in writing and their oral histories had gone unrecorded.

Four or five decades ago, several ancient Tswana ruins in and around the Suikerbosrand hills, about 60 kilometres south of Johannesburg, had been excavated by archaeologists from the University of the Witwatersrand. But from ground level and on aerial photos the full extent of this settlement could not be appreciated because vegetation hides many of the ruins.

But LiDAR, which uses laser light, allowed my students and I to create images of the landscape and virtually strip away the vegetation. This permits unimpeded aerial views of the ancient buildings and monuments.

We have given the city a generic placeholder name for now – SKBR. We hope an appropriate Tswana name can eventually be adopted.

Bringing the city to life

Judging by the dated architectural styles that were common at SKBR, it’s estimated that the builders of the stone walled structures occupied this area from the fifteenth century AD until the second half of the 1800s.

The evidence we gathered suggests that SKBR was certainly large enough to be called a city. The ancient Mesopotamian city of Ur was less than 2km in diameter while SKBR is nearly 10km long and about 2km wide.

It is difficult to estimate the size of its population. Between 750 and 850 homesteads have been counted at SKBR, but it’s hard to tell how many of these were inhabited at the same time, so we cannot easily estimate the city’s population at its peak.

Given what we know about more recent Tswana settlements, each homestead would have housed an extended family with, at the least, the (male) head of the homestead, one or more wives and their children.

Many features of the built environment at SKBR seem to signal the wealth and status of the homesteads or suburbs that they are associated with. For example, parallel pairs of rock alignments mark sections of passageways in several different parts of the city.

South African archaeologist Professor Revil Mason, who has carried out a great deal of research on stone walled ruins around Johannesburg, called these features cattle drives, built to funnel the beasts along certain routes through the city.

If these were cattle drives the width and location of these passageways would have signalled the livestock wealth of the ward or homestead that constructed them, even when the cattle were not present.

In the central sector of SKBR there are two very large stone walled enclosures, with a combined area of just under 10, 000 square meters. They may have been kraals and if so they could have held nearly a thousand head of cattle.

Monuments to wealth

Among the largest features of the built environment at SKBR are artificial mounds composed of masses of ash from cattle dung fires, mixed with bones of livestock and broken pottery vessels. All this material appears to have been deliberately piled up at the entrance to the larger homesteads.

These are the remains of feasts and the ash heaps’ size publicised the particular homestead’s generosity and wealth. The use of refuse dumps as landmarks of wealth and power is known from other parts of the world, like India, as well. Even the contemporary gold mine dumps of Johannesburg can be seen in this light.

Other monuments to wealth and power at SKBR include a large number of short and squat stone towers – on average 1.8 - 2.5 metres tall and about 5 metres wide at their base. The homesteads with the most stone towers tend to also have unusually large ash heaps at their entrance. The practical function of the towers isn’t known yet: they may have been the bases for grain bins, or they may mark burials of important people.

It will take another decade or two of field work to fully understand the birth, development and ultimate demise of this African city. This will be done through additional coverage with LiDAR, intensive ground surveys as well as excavations in selected localities.

![]() Ideally, the descendants of those who built and inhabited this city should be involved in future research at this site. Some of my postgraduate students are already in contact with representatives of the Bakwena branch of the Tswana who claim parts of the landscape to the south of Johannesburg. We hope that they will actively become involved in our research project.

Ideally, the descendants of those who built and inhabited this city should be involved in future research at this site. Some of my postgraduate students are already in contact with representatives of the Bakwena branch of the Tswana who claim parts of the landscape to the south of Johannesburg. We hope that they will actively become involved in our research project.

Karim Sadr, Professor Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, University of the Witwatersrand. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.