Africa is no longer the carbon sink of the world

- Wits University

In only nine years between 2010 and 2019, Africa has turned from being a net carbon sink, to being a net carbon source.

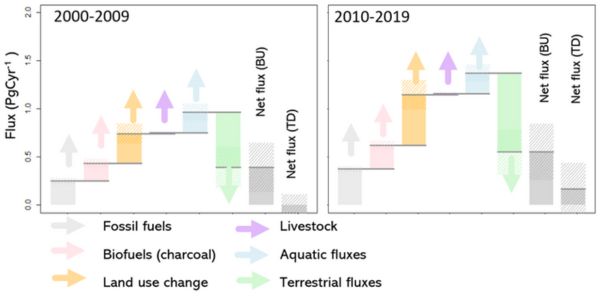

Figure 1: Summarising the key components of the African Carbon Cycle and their change over the first two decades of this century. Anthropogenic activities such as fossil fuel burning and agricultural activities release carbon dioxide and other GHGs into the atmosphere. Some of this carbon gets taken up again through ecological processes such as weathering and plant growth, so the net amount accumulating in the atmosphere is often less than the anthropogenic sources. Arrows up show sources to the atmosphere and arrows down show carbon being absorbed into the ecosystem. The coloured bars are the best available estimate, and hashed bars represent our uncertainty about that estimate.

New research by a team of researchers from the Futures Ecosystems for Africa programme, based at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, has found that in the years between 2010 and 2019, the continent of Africa has transitioned from being a slight net carbon sink to a slight net carbon source.

Overall, it is estimated that Africa is a source of 4.5 petagrams, or 4.5 billion metric tons, of carbon dioxide equivalents per year.

While, until now, Africa has been producing about 4% of the anthropogenic greenhouse gasses (GHG), that leads to climate change, globally, the continent has also been offering climate services to the globe, largely through the intact ecosystems in the tropics which have been sequestering more GHG’s than were released through anthropogenic activities. While it still serves this purpose, in the last decade the rate at which carbon is being released from the continent increased.

“In terms of global numbers this means Africa still hovers around 4% of fossil fuel emissions, but actually emits nearly 40% of the global emissions from land use, and is now, for the first time, contributing 3-5% of the growing amount of GHGs in the atmosphere,” says Professor Sally Archibald, Principal Investigator at the Future Ecosystems for Africa Program, and Professor in the Wits School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences at Wits University.

The population of Africa, the second-largest continent in the world, currently sits at about 1.4 billion, but is set to exceed 2 billion by 2040, the trend is likely to continue.

Key factors in the rise of greenhouse gases include fossil fuel burning, methane emissions from livestock, and soil carbon losses and nitrous oxide emissions as land is converted for agricultural use.

“While Natural ecosystems continue to act as carbon sinks across the region and are taking up about 30% of what is being emitted to the atmosphere through human activities, greater swaths of land than ever before are being used for agriculture, and livestock numbers are increasing, with the net result being that these changes in land use have affected Africa’s role in the global carbon cycle,” says Dr Yolandi Ernst, researcher at the Wits Global Change Institute and the lead author of the study.

To make their estimates, Ernst et al. followed the budget assessment protocol laid out by the REgionalCarbon Cycle Assessment and Processes (RECCAP2). They took a comprehensive look at all major potential carbon sources, including human sources such as agriculture and fossil fuel emissions and natural sources such as termites and wildfires. They also considered natural sinks: the grasslands, savannas, and forests that still cover much of the continent.

Figure 2: Some of the ecosystem processes that need to be quantified to accurately assess the African Carbon Budget – methane emissions from termites and livestock, as well as tree growth and mortality rates.

Overall, they estimated that Africa was a source of 4.5 petagrams, or 4.5 billion metric tons, of carbon dioxide equivalents per year, with land use emissions still being higher than fossil fuel emissions. Both are growing rapidly. In the last year, the total anthropogenic emissions (emissions resulting from human activity), including trade, livestock and fuel burning were estimated at 1.2 petagams of carbon per year. Moderate climate conditions and high productivity of the tropical forests helped natural ecosystems to take up about 0.6 petagrams of carbon per year, leaving approximately 0.6 petagrams of carbon as the net flux, released into the atmosphere.

Figure 3: Showing different forms of land use in Africa – as landscapes are transformed into small scale, and then commercial agriculture, GHG emissions and carbon losses increase significantly.

The information from this research on Africa’s carbon budget is key to identifying which aspects of the greenhouse gas cycle are most important to be managed in the quest to achieve net zero, and possibly restore the continent’s role as a carbon sink.

“Investing in carbon-neutral energy sources could reduce about 30% of Africa’s anthropogenic emissions, but novel ways to manage landscapes for livelihoods and carbon storage would be needed to slow the emissions from agriculture and land use,” says Ernst.

“As demand for food production increases, we need a focus on climate-smart agricultural practices on the continent, as well as a focus on investments that address socio-economic challenges in nature-preserving ways across Africa.”

“Protecting, managing, and restoring the landscapes that are helping to take up the excess CO2 is an important part of the solution - but there are challenges with making carbon storage the main goal of conservation and it can conflict with biodiversity and water provision. The Future Ecosystems for Africa Program is working with scientists, policy makers, and carbon projects across the continent to try to navigate this and identify opportunities to store carbon in natural ecosystems that do not damage the ecology.”, says Archibald.