Huge gap between SA's 4IR strategy and what commission recommends

- Barry Dwolatzky and Mark Harris

Huge gap between SA's 4IR strategy and what commission recommends

How will the recommendations of the Presidential Commission on the Fourth Industrial Revolution catapult South Africa? We find a huge gap between what we see on the ground and the recommendations of the commission.

The much-anticipated final report and recommendations of the Presidential Commission on the Fourth Industrial Revolution were officially gazetted and made available for public scrutiny in October 2020. In summary, the commission’s recommendations were:

- Invest in human capital development;

- Establish an Artificial Intelligence Institute;

- Establish a platform for advanced manufacturing and new materials;

- Secure and avail data to enable innovation;

- Provide incentives for future industries, platforms and applications of Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) technologies;

- Build 4IR infrastructure;

- Review and amend (or create) policy and legislation; and

- Establish a 4IR Strategy Implementation Coordination Council in the presidency.

Reading these proposals together with the far more detailed description of each in the final report, we ask the question: How will this catapult South Africa into the 4IR? We find a huge gap between what we see on the ground and the recommendations of the commission.

What is it that we see on the ground? Let us look through one of many specific lenses. We have chosen to examine our criminal justice system.

The Integrated Justice System

Penuell Maduna was minister of justice in President Nelson Mandela’s Cabinet between 1994 and 1998. In 1996, he presented his department’s vision for an integrated “E-Justice” system at a local IT conference. It was the first time that some of us, who are now veterans of the South African IT industry, heard about the “Integrated Justice System”.

Today, on the government’s official website, the objectives of this system are described as follows:

“The Integrated Justice System aims to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the entire criminal justice process by increasing the probability of successful investigation, prosecution, punishment for priority crimes and, ultimately, rehabilitation of offenders. Further issues receiving specific attention include overcrowding in prisons and awaiting-trial prisoner problems, as well as bail, sentencing and plea bargaining.”

What should an “integrated justice system” in 2021 look like? Imagine the following hypothetical scenario:

My car was stolen while I was visiting a friend in Norwood, Johannesburg. As soon as I noticed it was missing, I phoned the emergency call centre. I spoke to a chatbot, which captured the relevant information in less than a minute. A digital crime report was logged in a central cloud-based system and I received an SMS with my case number. I forwarded this to my insurance company. My licence plate number was uploaded on to the centralised “stolen vehicle” database and an alert was issued to hundreds of smart cameras in the area. Each camera is equipped with Licence Plate Recognition software.

Within a few seconds, an operator at the Johannesburg central control centre was alerted to the fact that my stolen vehicle was parked outside a small industrial building in Jeppestown, east of the city centre. A live image was brought up on her screen showing two men standing next to the vehicle. She zoomed in on their faces and sent their images to the integrated facial recognition system. Within two minutes, she had information on one of the two men. He had a previous conviction in Durban for receiving stolen vehicles. The system had already automatically dispatched a police patrol car and connected the crew via a secure radio link to the control centre operator.

Five minutes later, the patrol vehicle reached the building in Jeppestown. The control centre operator, still watching the scene live on her screen, directed them to a lane at the side of the building where they found a group of men beginning to strip down my vehicle for spare parts. Three men were arrested and two escaped through a back entrance. These two were identified via images received from the bodycams worn by the police officers. They were arrested later in the day.

When the men appeared in court a week later, the prosecutor pulled up the digital docket on his laptop. He had video and stills images captured by security cameras and from the bodycams of the police officers. He also had full details of previous convictions of some of the accused. Within an hour all accused had been convicted and sentenced.

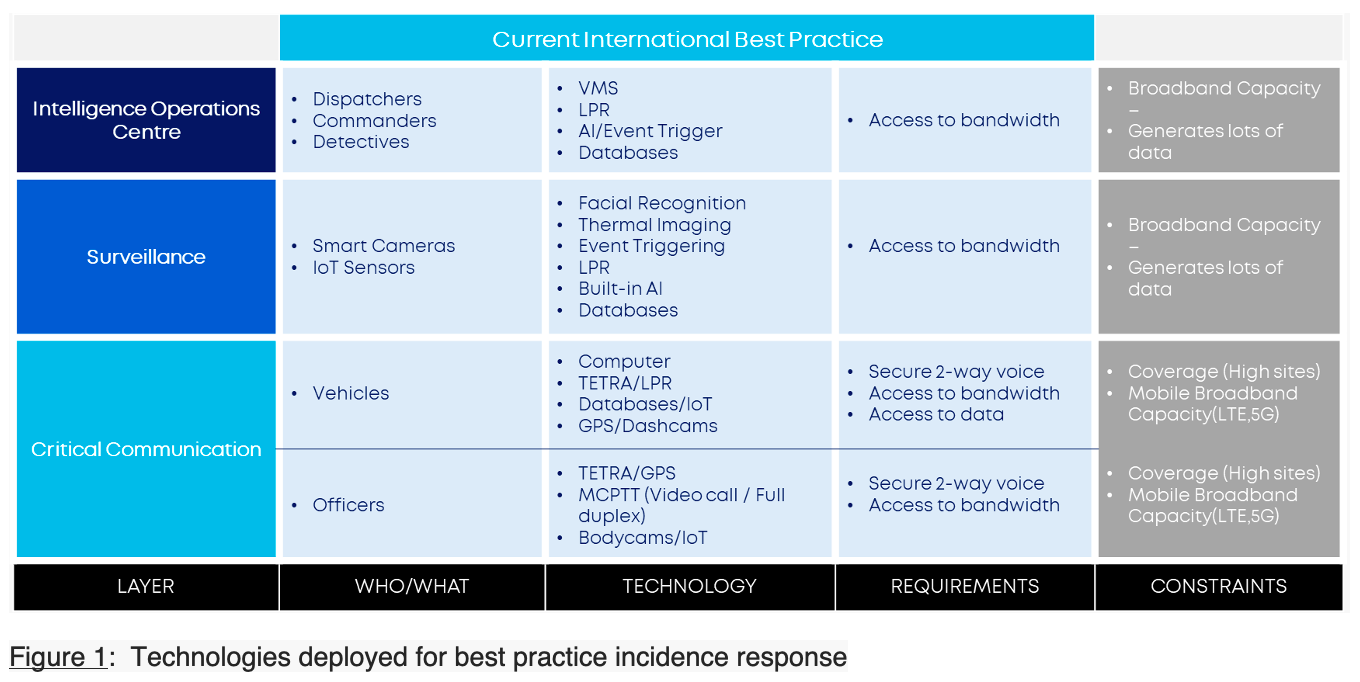

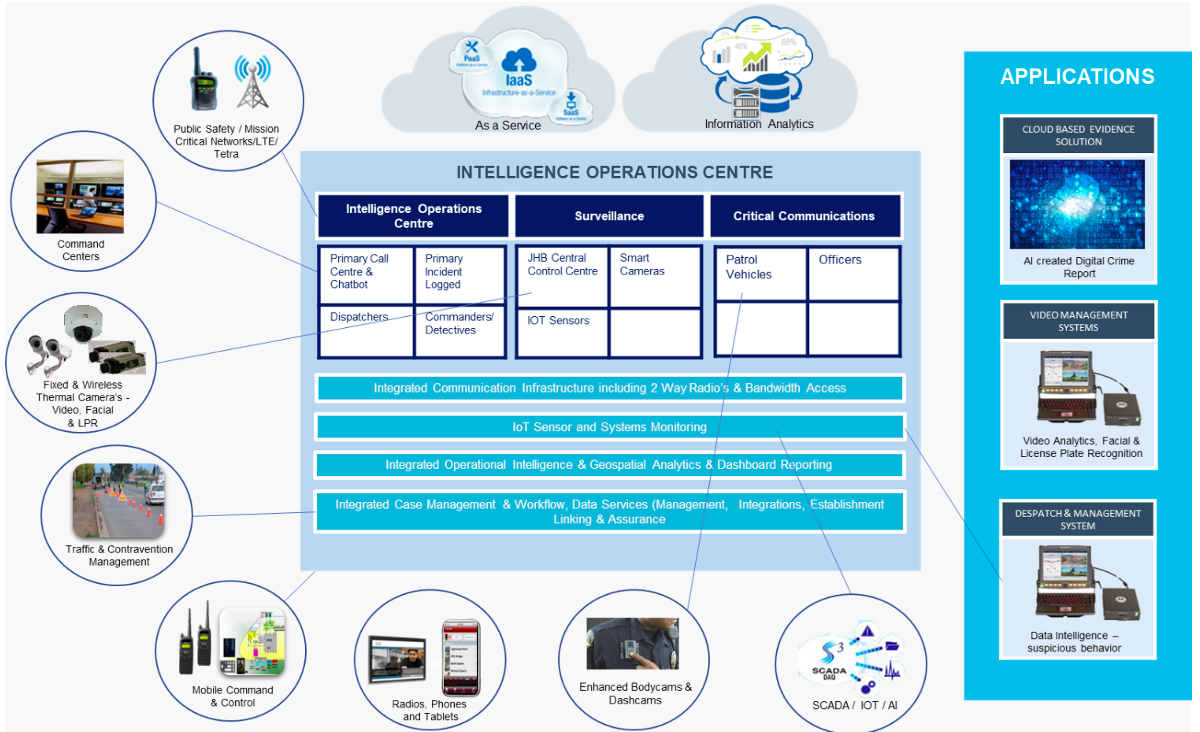

The diagram in Figure 1 represents the technology and systems that would need to be in place to make the scenario set out here a reality.

From this diagram one will see, at the lowest level, first responders, namely police officers and patrol vehicles, are equipped with mobile critical communications infrastructure. They have access to digital radio communication using the Tetra (Terrestrial Trunked Radio) standard, which provides highly secure two-way voice with GPS location and limited data communication independent of public mobile networks.

Officers also wear bodycams that can be viewed live and vehicles are equipped with dashcams. Officers may also carry wearable Internet of Things-based sensors (for example, GPS). The onboard computer in the patrol vehicle has access to Licence Plate Recognition software and a variety of data sources on the cloud.

At the next level is surveillance technology consisting of smart cameras and Internet of Things sensors. The smart cameras have built-in artificial intelligence (AI) capability, such as Licence Plate Recognition, and can access information via the cloud. They can also detect “unusual behaviour”, such as the same car passing several times, and will trigger an event that notifies the operations centre.

At the highest level is the Intelligence Operations Centre. It is equipped with AI-based software systems and a sophisticated video management system. Personnel in the centre include dispatchers and commanders who can coordinate first responders and back-up teams, and detectives who coordinate collection of evidence.

All of these systems, from the first responders on the ground to the Intelligence Operations Centre, require reliable, secure communications and high-capacity broadband connectivity.

Anyone who has engaged with the South African criminal justice system will know that the description above remains a distant vision. Have you tried reporting a burglary or a stolen car at your local police station? And what if the burglar is apprehended? Have you sat in court months later ready to give evidence only to hear that either the docket or the accused is “missing”?

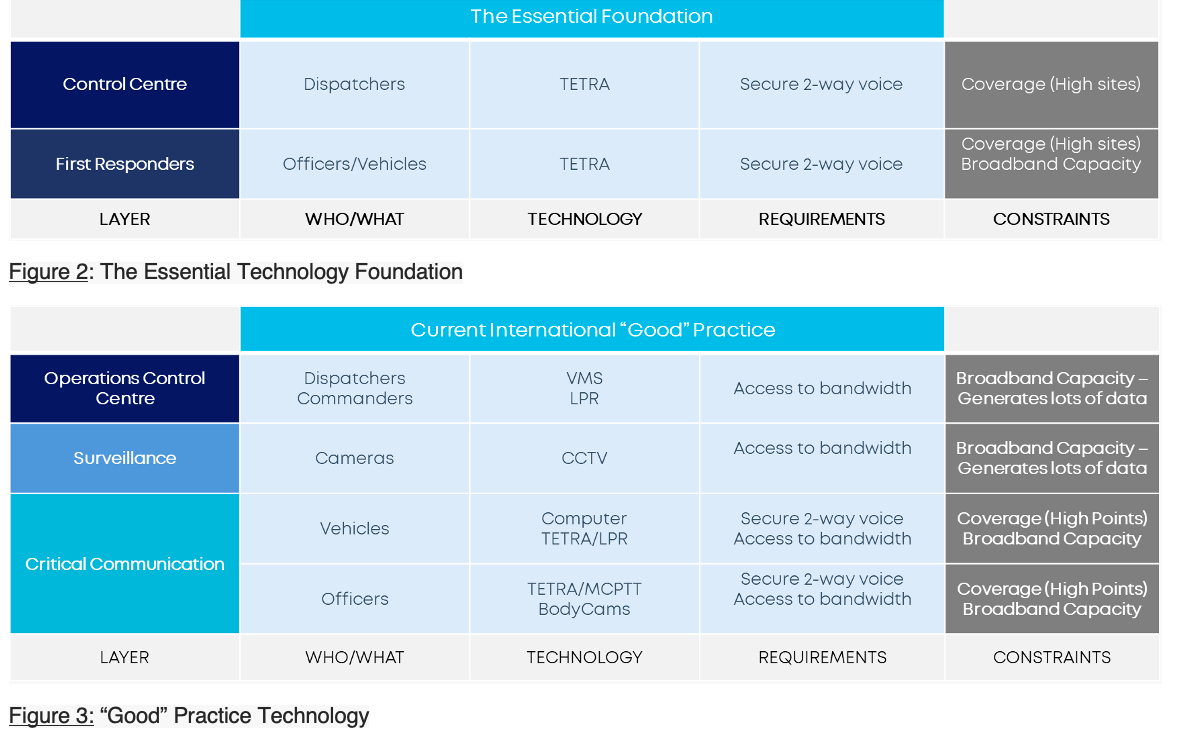

In our current system, processes are largely paper-based and manual. Where digital systems are in place, they are outdated and non-integrated. In terms of technology used in crime-fighting, our police systems lie somewhere between the representation in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

The scenario above and the representation in Figure 1 is, however, not fanciful and futuristic. Cities around the world implemented such systems several years ago and some are in the process of adding further levels of integration and intelligence.

Using technologies such as AI, machine learning, Internet of Things, cloud computing, robotic process automation, drones and advanced image processing, coupled with the drawing in of data from multiple sources including cellphone networks and social media platforms, the fight against crime is reaching the highest level of sophistication.

We would argue that the scenario we have presented here, together with its future possibilities, is what the 4IR would look like through our lens of the criminal justice system.

We do acknowledge, however, that while our focus is on the advantages derived from the technology described, there is another side to the coin of increased surveillance and monitoring. The disadvantages of these technologies in terms of civil liberties and privacy might in some cases outweigh their advantages.

The gap between where we are and the 4IR

Why is South Africa lagging behind, and why is it that 25 years after Maduna announced the launch of the Integrated Justice System for South Africa, we still read about it as a statement of future intent on our government’s website?

There are several reasons for the lack of progress on the implementation of the Integrated Justice System.

The vision doesn’t go far enough. Government is still working painfully slowly to deliver a system offering the level of functionality that might have been seen as cutting edge in 2010. The vision, design and architecture of the system need to be constantly updated to reflect rapidly emerging technology trends.

There is a reluctance on the part of staff in the relevant departments and their labour unions to adopt new technology. There is also a shortage in these departments of the relevant skills.

At the heart of an integrated system such as the Integrated Justice System is the need for excellent connectivity at a low cost. Every point of contact in the system, from police stations to court rooms to prisons to patrol vehicles and individual officers, to cameras and central control rooms, must be equipped with a fast and reliable broadband connection. These links must be secure.

Such connectivity does not exist, even in our major metropolitan areas. Many implementation projects have failed due to connectivity issues.

The other need is for data management. The integration of the Integrated Justice System is its most important requirement. For this to be achieved, common data standards and management protocols must be defined and implemented.

Tendering and procurement processes within government tend to slow down and block innovation and implementation. Red tape, inefficiency and – sometimes – corruption have bedevilled many critical government IT projects over the past 25 years.

What does this say about the 4IR in SA and the recommendations of the presidential commission?

We would argue that a successful transition to the 4IR would look like the vision we have painted for the Integrated Justice System.

One could create similar scenarios for other clusters in our economy, such as education, health, logistics, and so on. In each case, we would expect to see seamless integration of processes supported by data, automation and advanced technologies such as AI.

We do not believe that the recommendations submitted by the Presidential Commission on the Fourth Industrial Revolution provide a road map for moving us from where we currently are (somewhere between Figure 2 and Figure 3) to where we want to be (Figure 1 and beyond).

Let us very briefly consider each of the commission’s eight recommendations in relation to the advanced Integrated Justice System outlined above:

- Invest in human capital development: while skills are a constraint in implementing the full Integrated Justice System, the reluctance of existing staff, supported by their unions and associations, to adopt new digital technology and accept reskilling is the bigger constraint;

- Establish an Artificial Intelligence Institute: the role of such an institute would be developing skills (see previous point) and new cutting-edge AI-based technology. As we have shown, existing technologies exist and while it would be important in the future to develop our own technological solutions, we have struggled to even adopt off-the-shelf AI technologies;

- Establish a platform for advanced manufacturing and new materials (this is not relevant to the Integrated Justice System scenario);

- Secure and avail data to enable innovation: availability, management and integration of data would move us closer to our 4IR goal;

- Provide incentives for future industries, platforms and applications of 4IR technologies: again, the problem is not innovation, but is rather implementation;

- Build 4IR infrastructure: Since this includes fast and affordable broadband connectivity and cloud infrastructure, this is an important and relevant recommendation;

- Review and amend (or create) policy and legislation: one of the constraints in the Integrated Justice System has to do with procurement and tendering. This is a relevant recommendation; and

- Establish a 4IR Strategy Implementation Coordination Council in the presidency: while this might help, its mandate and powers are unclear. Would this council, for example, be able to unblock obstacles that have made the implementation of the Integrated Justice System so difficult? We are not convinced.

We believe that the presidential commission should have looked through specific lenses, as we have done in this article, and developed concrete recommendations on how to move rapidly to the 4IR scenarios, such as the one we have presented.

Professor Barry Dwolatzky is Emeritus Professor at the University of the Witwatersrand and Director of the Joburg Centre for Software Engineering. Mark Harris is CEO of Altron Nexus. This article was first published in Daily Maverick/Business Maverick.