Wits at a time of national crisis: Then and now

- Professors Jacklyn Cock and Eddie Webster

South African universities should revisit their multiple publics and explore what a public university in southern Africa today should be.

In 1986, Wits initiated the?Perspectives of Wits (POW) project to explore township communities’ perceptions of the University. Professors Jacklyn Cock and Eddie Webster suggest that we revisit how Wits is perceived in the 21st Century in the context of climate change and persistent inequality.

As the number of black students increased at Wits University in the 1980s, township struggles spread onto the campus and management came under increasing grassroots pressure to implement change within the University. In response, social scientists in the Faculty of Humanities, with the financial support of the University’s Research Office, undertook an extensive survey of the perception of Wits among organisations in Gauteng townships, as well as of international academics, students and staff at Wits, and even had a meeting with the then-banned African National Congress (ANC) in Lusaka.

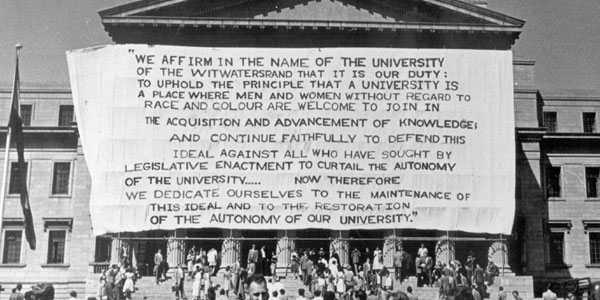

The outcome of this?Wits-initiated research project,?Perspectives of Wits, published at the height of apartheid in 1986, revealed a disconnect between township communities’ perceptions of Wits, and the image that the Wits administration had been attempting to convey of the University as a progressive opponent of apartheid.

The POW survey revealed that a large proportion of the community members surveyed thought that Wits served mainly white, corporate interests. The report recommended widespread further transformation of the University.

Knowledge for whom, for what, by whom?

Nearly 40 years later, with University leadership, staff and students increasingly representative of South Africa’s demography, Wits has clearly made significant progress towards what the late anti-apartheid cleric Reverend Beyers Naudé called for at the time, “securing a democratic, educational future for all in South Africa”.

However, we must ask whether the University’s responses to the multiple crises we face today are not reproducing a similar disconnect between the University and the growing number of students struggling to pay their fees, amidst the impoverished and hungry masses eking out an existence in the sprawling informal settlements in Gauteng.

Do we need another survey to establish whose interests and needs we are serving? This survey needs to be framed by three crucial questions: Knowledge for whom? Knowledge for what? And knowledge by whom?

Mind the mines

These questions are of relevance because of our long-standing relationship with the mining industry.

Indeed, our origins go back to the South African School of Mines, established in Kimberley in 1896. At the time of the POW survey, the Chamber of Mines – and Anglo-American in particular – remained our largest private donor. Of course, there have been occasions in our history when the Chamber felt that it was not receiving a satisfactory return on its investment in the University. An example was the attempt by the asbestos industry to suppress the findings in the 1950s by the Wits Pneumoconiosis Unit of a link between asbestos and cancer – the hidden disease of mesothelioma. On balance, however, it can rightly be claimed that Wits has served mining capital well over the years.

Today, extractivism – the process of extracting natural resources from the Earth to sell on the world market – particularly of coal, is under attack because of its relationship to the crises of climate change and deepening inequality. As in the past, there are a variety of responses to these crises amongst Wits’ diverse constituencies. The establishment of the Southern Centre for Inequality Studies and the recent appointment by Wits of a Pro-Vice Chancellor on Climate, Sustainability and Inequality is an exciting response that places Wits at the forefront of two central national challenges: climate change and the persistence of our position as the most unequal country in the world in terms of income and wealth.

These high levels of inequality have been sustained, and in some cases have deepened in the post-apartheid era. Will our researchers help promote a shift in the dominant view of coal as a source of energy, jobs and foreign exchange, to the view that coal is a driver of inequality and environmental damage? Will we help promote a democratic “just transition” from coal, which includes the lived experience of people in coal-affected communities? In the present cacophony of voices addressing the question of a just transition, we hope that these marginalised voices will be heard.

Commodifying knowledge

Much has changed over the past four decades as Wits and universities globally have been restructured according to a market logic. This means that knowledge is largely valued in terms of its capacity to be commodified. As universities have been defunded by the state, funds have been sought through raising student fees, the provision of short and online vocational courses, trusts and foundations, and endowments from wealthy alumni.

One of Wits’ biggest mistakes, which it has since rectified, was to try to cut costs by outsourcing its service staff to avoid paying benefits. Furthermore, over time, the balance of power has shifted from academics to the administration as a form of academic managerialism triumphed and Senate was in danger of being side-lined. The Senate is accountable to the Council for regulating all teaching, learning, research and academic functions of the University and all other functions delegated or assigned to it by the Council.

The Australian academic Jill Blackmore suggests that this market logic “results in epistemic injustice … it ignores the social and material conditions of knowledge production – the social relations of collegiality and collaboration, the emotional labour of teaching and researching” that is “dangerous for democracies”.

As Wits proudly celebrates a century of independent critical thought, maybe we need to revisit our external stakeholders to see how they perceive us in the face of the multiple crises of increasing inequality, casualisation of labour and ecological devastation?

Indeed, is it not time for all South African universities to revisit their multiple publics and explore with them what a public university in southern Africa in the 21st Century could – and should – become?

Jacklyn Cock is Professor Emeritus in the School of Social Sciences and Edward Webster is Professor Emeritus in the Southern Centre for Inequality Studies. They were members of the Perspectives of Wits research team in the 1980s and remain active researchers at Wits today.

This article first appeared in?Curiosity, a research magazine produced by?Wits Communications?and the?Research Office. Read more in the 14th issue, themed: #Wits100 where we celebrate a century of research excellence that has shaped today and look forward to how our next-generation researchers will impact the next 100 years.